Postcolonial Congo -A Country and Region at War

The previous activity details the events leading up to the Great African War, a time of conflict in the Congo.

The Great African War: Part One (October, 1996 – May, 1997)

The invasion of eastern Zaire in October 1996 by a multinational force led by Rwanda (with support from Uganda and Burundi), including militia affiliated with the AFDL led by Laurent Kabila and local militia comprised of Banyamulenge (Congolese Tutsis), initiated the conflict that has lasted, through three distinct phases –with reduced intensity since 2007, and continuing in isolated pockets as late as 2016. During the Great Africa War, as it has been called, upwards of five million people have died, millions more have been displaced, the surviving population has suffered much social and economic deprivation, and the eastern Congo has been without anything approximating an effective government.

The incredible suffering that has occurred in the eastern Congo over the past two decades has few parallels anywhere else in the world in the post World War II era. Yet, outside the region, this tragedy has not received much attention. When the Western press has reported on the conflict they have generally resorted to inadequate, and often inaccurate, explanations that ignore the historical complexities detailed above but are rooted in the stereotypes that much of the West has had of Africa for more than a century. In this regard, prior to cataloging the history of this conflict, it is helpful to give attention to Jason Stearns’ introduction to his study of the war and its consequences.

[Western] news reports from the Congo still usually reduce the conflict to a simplistic drama. An array of caricatures is often presented: the corrupt Africa warlord with his savage soldiers, raping and looting the country. Pictures of child soldiers high on amphetamines and marijuana—sometime form Liberia and Sierra Leone, a thousand miles from the Congo. Poor black victims: children with shiny snot dried on their faces, flies buzzing around them, often in camps for refugees are internally displaced. Between these images of killers and victims, there is little room to challenge the clichés, let alone try to offer a rational explanation for a truly chaotic [& complex] conflict. The Congo wars are not stories that can be explained through such stereotypes. They are the product of a deep history, often unknown to outside observers. The principal actors are far from just savages, mindlessly killing and being killed, but thinking, breathing Homo Sapiens, whose actions, however abhorrent, are underpinned by political [and economic] rationales and motives. ” (Pg. 4).

It is the objective of this lesson to offer a more comprehensive and nuanced analysis of the conflict in eastern Congo than that which has been represented in the media.

The first phase of the Great African War lasted just under a year. The primary objective of the instigators of the conflict, the AFDL, and its external sponsors (Rwanda and Uganda) was the demise of the Mobutu regime and the establishment of a new government in Kinshasa that would be closely aligned to their interests. The earliest skirmishes took place in South and North Kivu provinces with troops affiliated with the AFDL and local Banyamulenge militia, with strong support from the Rwandan, Ugandan and Burundian armies, leading the offensive. By early 1997, as this coalition of forces moved out of the Kivu provinces, first to the south into Shaba (Katanga) province and then to the north and northwest in Orientale and Maniema provinces, the AFDL coalition was joined by troops and air support from Angola and militia from southern Sudan (now South Sudan, which became independent from Sudan in 2011) along with important materiel support from Namibia and Zimbabwe.

First war 1996-97

Belligerents:

I. President Mobutu and his waning domestic supporters including army and specialized militia

a. Foreign Allies:

i. African:

1. Sudan

2. Central Africa Republic

3. UNITA (Angola resistance movement)

ii. Outside Africa:

1. France (covert), opposed to growing Anglo influence in Rwanda

2. Israel (covert)

II. Laurent Kabila and his Alliance des forces pour libération du Congo-Zaire (AFDL)

a. Foreign Allies:

i. African:

1. Rwanda

2. Uganda

3. Burundi

4. Angola

5. Ethiopia

6. South Sudan rebels

7. Zimbabwe

8. Zambia (low level engagement)

9. Tanzania (low level engagement)

ii. Outside Africa:

1. U.S. (covert)

The Mobutu regime’s response to the invasion from outside had to depend an army severely demoralized and weakened by more than a decade of neglect with limited loyalty to Mobutu who had few external friends who were willing to come to his aid. Only the Sudan and the Central African Republic were willing to provide minor support for the rapidly crumbling Mobutu regime. By the mid-May 1997, less than a year after the initial AFDL invasion into eastern Congo, Mobutu had fled the country and AFDL forces had gained control of Kinshasa. On May 19, 1997, Laurent Kabila was declared president of the renamed Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Although the advance across the Congo by AFDL and allied forces was rapid, it was none-the-less brutal, setting a precedent for the violent warfare that has plagued the Congo for the past 20 years. The initial invasion in October 1996 received very limited opposition from the official Zairian army battalions stationed in the Kivus. However, the attacking forces’ primary objective in this region was not just the army but, more importantly, the Interahamwe and Rwandan refugees (primary Hutu) in eastern Congo. The post-genocide Rwandan regime, that had created the AFDL, was determined to destroy the Interahamwe along with any perceived threat within the large refugee community. Consequently, many thousand refugees, most of whom were innocent of participating in the resistance to the new government in Rwanda, were killed. This history is not widely known outside of academic, human rights, and international aid communities who work in the area. Western governments, including the U.S. government, were reluctant to criticize the actions of the AFDL and its Rwandan backers, excusing this action as an understandable, if over-zealous, response to the genocide. Some concerned western observers have accused western governments of being complicit in the violence, asserting that the Clinton administration, in particular, refused to intervene because of feeling great guilt for not having intervened to stop the genocide in Rwanda.

The often horrendous actions of the AFDL forces and their external allies continued as they progressed across the country, with the seeming objective of completely destroying potential opponents, real and imagined.

The AFDL, from the first days in power in Kinshasa, made it clear that they were not interested in constitutional reform. They asserted that years of political chaos and the decay of the state structures necessitated strong, focused leadership, and Kabila was declared president with extensive, if not absolute, political power. He was given the authority to make laws (making no attempt to establish a legislature) and executive degrees that had the force of law. He had the power to appoint and dismiss cabinet members, ambassadors, judges, and senior military officers. The AFDL made no attempt to establish a national government of reconciliation by inviting individuals who had formed the internal opposition to the Mobutu regime. Nor did Kabila make any attempt to reach out to the active Congolese exile community who had for decades led the active external opposition to Mobutu from other African countries, Belgium, France and the U.S. These earlier actions laid a foundation that was antithetical to the development of inclusive, democratic institutions in the Congo.

Leading up to the AFDL take over in Kinshasa, Kabila had maintained that once in power, the AFDL would begin to set in place a socialist type of economic system in which the government would actively invest in and take control over major economic assets, such as the mines in Katanga, using this control to benefit all of the citizens of the Congo. This commitment was consistent with Kabila’s long-standing (dating back to the 1960s) identification with socialism. However, once in power, the AFDL did not attempt to set up mechanisms to engage the government in the economy, such as the nationalization of mines. Instead, Kabila, and his top associates, initiated a process of distributing economic assets to top AFDL affiliates and seeking foreign investments from businessmen who were given access to Congo’s natural resources on very favorable terms, in return for generous kickbacks to senior government officials. As will be detailed in the final section of this activity, these actions set in place a practice that has caused great economic suffering in the Congo and has perpetuated the poverty and underdevelopment of one of most well-resourced countries in the world.

The Great Africa War: Part Two (1998 – 2003) “Can a toad sallow an elephant?”

Within a year of Kabila’s taking over the presidency of the newly renamed Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which marked the end of the first phase of the Great Africa War, Rwandan and Ugandan troops, his former allies who brought him to power in the DRC, were masterminding yet another invasion of the country with the aim, this time, of ousting Kabila. This most destructive phase of the war would last five years.

What went wrong with the relationship between these former allies that resulted is the rapid deterioration in the alliance? It is fair to state that the relationship between Kabila and Rwanda and Uganda was from the beginning based on mutual distrust and suspicion. As detailed in the previous section, the Rwandans and Ugandans were in early 1996 desperate to recruit a Congolese who had some legitimacy as a nationalist opponent to Mobutu to “lead” their efforts to overthrow Mobutu and to contain, if not destroy, Hutu militia in eastern Congo, whom they viewed as an existential threat to the post-genocide regime in Rwanda. Kagame and Museveni wanted a compliant leader for the movement to oust Mobutu and establish a Rwanda and Uganda friendly regime in Kinshasa.

Kabila never bought into this scenario. He was not interested in being the puppet of Rwanda and Uganda. However, since he was completely dependent on these countries to gain control of the Congo, Kabila was forced to demonstrate loyalty to and compliance to Kagame and Museveni until he took power in Kinshasa. However, within months of coming to power, Kabila began to exert autonomy from his former benefactors. In exercising his independence, Kabila had wide support in the Congo, particularly in the capital city where residents were offended by the presence of Rwandans, and eastern Congolese of Tutsi heritage, whom accompanied Kabila to Kinshasa and who occupied many of the senior positions in the army and police force. Many locals viewed them as an occupying force.

In July 1998 Kabila sacked the Rwandan chief of staff of the Congolese army. The residents of Kinshasa took this action as giving them license to protest the presence of Rwandans and Congolese Tutsi in the capital city. In response to perceived threats in late July, Rwandan and Congolese Tutsi troops took control of the major army base in Kinshasa. However, they did not attempt a coup to dispose of Kabila and take control of the government. Kabila responded, on July 28th by ordering all Rwandan and Ugandan troops to leave the Congo.

In early August, the Rwandan and Ugandan governments responded by invading eastern Congo for the second time in as many years; the first time had been in support of Kabila and the AFDL, the second time in an effort to oust Kabila and replace him with a government that would be more amenable to the interests of their regimes. As was the case in 1996 the invasion was supported by local Tutsi militia, the Congrés National Pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP) and by a newly established opposition group, the Rally for a Democratic Congo (RDC), which was created to establish legitimacy for their invasion. In 1996 they had selected Kabila to lead the AFDL; this time around they recruited professor Wamba dia Wamba, who, unlike Kabila, had credibility among the Congolese exile communities as well as within the Congo, to be the leader of the RDC.

Before the end of 1998, the coalition of Rwandan and Ugandan troops along with the CNDP and RDC militia were able to gain control over both north and south Kivu provinces and were moving to the north-west to take control of Kisangani, the fourth largest city in the Congo.

Given the ease of gaining control over eastern Congo, Col. Kabarebe, who was in charge Rwandan/Ugandan forces, became overly ambitious. He thought that the easy victories in the east indicated that the rest of country would fall with minimum intervention. Consequently, he allowed a top commander in the invading forces, Major Butera, to commandeer a jet in Goma to fly with 180 soldiers all the way across the country to an air base at Kitona, a base on the mouth of the Congo River. They took the base with minimum resistance. They thought that this victory would allow them to cut off the supply route from the Atlantic Ocean to Kinshasa, the capital city. However, they had not taken into account the likely reaction of the Angolans whose borders to the south and north (Cabinda) are less than thirty miles, or “spitting distance” according to an Angolan general, from the base at Kitona.

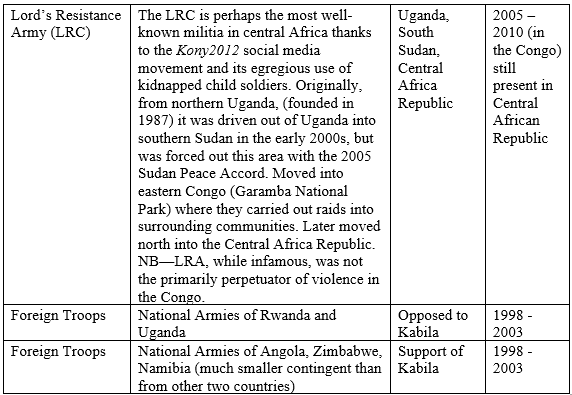

Armed Groups in Congo Conflict: Great African Wars: 1997 – 2017

By October 1998, it seemed possible that the coalition of external and internal militia might succeed in gaining control of the country before the end of the year. Kabilia’s hold on power in Kinshasa was tenuous even prior to the invasion. As discussed in the last section, when he took control of the country he did little to rebuild the institutions of governance that had been decimated by Mobutu’s dictatorship, nor had Kabila taken concrete actions to rejuvenate the economy. Moreover, by dismissing the senior leadership of the army, most of whom were Rwandans or Congolese Tutsis, Congo was without a functioning army, which could be called upon to resist the invading forces. However, he did have one factor going for him: powerful friends in neighboring countries.

This was particularly true of Angola, Congo’s southern neighbor who had less than two years earlier played a key role in the over throw of Mobutu and the instillation of the Kabila—and who, after decades of civil war and with significant oil wealth had a large and battle tested armed forces (third largest in sub-Saharan Africa after Nigeria and South Africa). Angola was offended right from the beginning of the second phase of the war, when Rwandan troops captured the air base at Kitona –“within spitting distance” of the Angolan border to the South and Cabinda to the north. Angolan President José Eduardo Dos Santos and the leadership of the ruling party (MPLA) clearly indicated that they were insulted by the actions of Rwanda and Uganda and committed troops to defend the Kabila regime.

The DRC is a part of the twelve member Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), one of the most important regional alliances in Africa. In early September, 1998 Congo appealed to SADC for support against the invasion by two non-SADC countries, Rwanda and Uganda. It is important to remember that two years earlier in 1996 five SADC countries (Angola, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe) had supported external intervention to oust Mobutu. It was a different story two years later in September 1998, when in spite of two back-to-back meetings of SADC presidents, there was no consensus within the alliance supporting invention in the Congo. Fortunately for Kabila, three SADC members, Angola, Zimbabwe and Namibia agreed to intervene in the Congo. These countries supplied the majority of external forces that defended the Kabila regime from 1998 – 2003. Indeed, without the active intervention of these countries the Kabila regime would not have survived.

Along with Angola, Zimbabwe became deeply enmeshed in the Great Africa War, sending and supporting thousands for troops into the Congo where they faced front line engagement with Rwandan and Ugandan troops and militia affiliated with the RDC and the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo (MLC). President Mugabe had mixed motivation for engagement in the Congo. Firstly, Congo owed Zimbabwe money for an agreed upon repayment for Zimbabwe’s support of Kabila’s successful effort to overthrow Mobutu. Mugabe feared that if Kabila was overthrown the substantial debt would not be repaid. Secondly, Zimbabwean businesses, many with close association with senior military leaders, were interested in “investing” in Congo’s vast mineral resources; Kabila had promised mining concessions in return for military support from Angola and Zimbabwe. Thirdly, Mugabe had lost position of prestige and power within SADC region when Nelson Mandela became president of a democratic South Africa in 1994. Mugabe believed that a successful foreign intervention would help him reassert his regional leadership credentials. Fourthly, Mugabe was facing consequences of far-reaching land reform at home—reduced revenues (replaced with hope for mineral revenues/spoils of war), and foreign intervention took public attention away from the negative impact land reform at home.

The Kabila regime in the Congo was saved by the intervention from southern neighbors. However, while the troops from Angola, Zimbabwe and Namibia were able to stop the advance of the coalition troops led by Rwanda and Uganda with support from Congolese militia, most import of which were the CNDP, MLC and RDC, Kabila’s external allies were not able to defeat these forces.

Main Belligerents in Second War (1998-2003)

I. Laurent Kabila and the Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDRC) allies:

a. Angola

b. Namibia

c. Zimbabwe

d. Anti-Rwanda militia in eastern Congo (Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)

II. Rwanda and Uganda allies (Congolese militia supported by Rwanda and Uganda):

a. Ressblement congolais pour la democracy (RCD, Rwanda)

b. Mouvement de libération du Congo (MLC, Uganda)

c. Ressblement congolais pour la democracy-Mouvement de libération (RCD-ML, Uganda)

By November 1998, Uganda had lost confidence in the RCD (and a rift had begun to surface between the two allies, Rwanda and Uganda). Uganda threw its support behind a rising “war lord” in north central/eastern Congo, Jean-Pierre Bemba (son of a wealthy Congolese businessman who had been an ally of Mobutu, and a multi-millionaire in his own right) and his MLC (Mouvement de libération du Congo). Bemba benefited from materiel and logistics support by Uganda, but, unlike most of the other Congolese militia, the MLC maintained a large degree of autonomy. By 2000 the MLC had a fairly well trained and disciplined militia that with support from Uganda was able to gain control of much of north central and northwestern Congo for its base in Gbadolite, Mobutu’s former stronghold.

In spite of furious and brutal battles, a stalemate came into place in late 1999 that lasted until the Sun City Settlement in April, 2003. As detailed in Map 3, the Congo was effectively divided into three zones: Rwanda and its RCD allies—the provinces of South Kivu, North Kivu, Maniema, the eastern third of Kasai-Oriental, and north east Katanga; Uganda and its MLC allies—the provinces of Oriental and most of Equateur; the Kabila government with the invaluable assistance from Angola, Zambia and Namibia, controlled the remainder of the country.

While most of the brutality of the Great Africa War was limited to the eastern third of the country, the war impacted all of the Congo. In the western two thirds of the country, the realities of the war effort meant an ineffective government, with no revenue to invest in desperately needed social, economic and infrastructural projects. Laurent Kabila, who was briefly popular after the departure of Mobutu, was widely disliked by Congolese by 2000. Inflation rate was over 500% and unemployment extremely high. Economic policy did not allow ordinary citizens to keep foreign exchange for more than five days, moreover Kabila kept the Congolese francs at an artificially high value—the official exchange rate for Congolese franc to US $ was 500 to one, but the parallel market rate was more than 2000 to one in 2000 CE.

Joseph Kabila, who replaced his father as president after the senior Kabila was assassinated in January 2001, was even more unpopular than his father; he lacked any legitimacy the elder Kabila had garnered by his leadership in overthrowing Mobutu. Joseph Kabila’s only political asset was that he was his father’s son.

The incredible suffering caused by the war, the continued political and economic decay, in combination with the war-weariness of the external powers that were deeply enmeshed in the conflict, provided an impetus for reaching a permanent settlement to the conflict. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) had, you will remember, attempted to negotiate an end for the conflict from the beginning of the conflict in 1998. However, selfish interest of each of the stakeholders, precluded serious peace negotiations from taking place until 2002.

By 2002 all of the major stakeholders recognized that it was in their best interest to seriously negotiate a peace settlement. Although Rwanda and Uganda were gaining economically from the illegal trade of minerals from eastern Congo, they recognized that they would not be successful in defeating the Kabila regime. Moreover, both Kagame and Museveni needed to pay closer attention to domestic issues in their own countries.

Kabila’s external allies were equally disillusioned by the stalemate in the Congo. Angola saw no incentive to funding a chronic conflict that was unpopular at home due to the loss of Angolan soldiers. Mugabe and the Zimbabwean generals, who had hoped for an economic bonanza from their engagement in the Congo, came to the bitter realization that the anticipated economic payoff would not happen. Moreover, even more than Angola, the Zimbabwean leadership faced growing opposition at home to a military adventure that the citizens viewed as fool-hearty.

The peace efforts in 2002, the Inter-Congo Dialogue, were spearheaded by South Africa under the leadership of Thabo Mbeki who had replaced Nelson Mandela as president in 2000. The negotiations that lasted nearly a year took place in the South Africa resort of Sun City. Mbeki, was a much more involved in negotiations than Mandela had been. He was willing to “bully” and threaten parties into agreement, after many walk-outs by various parties that stalled the negotiations. Finally, in April, 2002, the warring parties signed the AGI (Global and Inclusive Accord/Accord global et inclusive).

Joseph Kabila and his closest political supporters had the most to gain from a political settlement. A stalemate, while not in any regards a victory, did favor the political status quo in the country. It was not surprising that Kabila was able to remain in power (until today in early 2017) as a result of the peace settlement, even though the violence continued at a reduced level, and he has not been able to establish and effective government in the Congo.

The AGI allowed Kabila to remain as president until elections could be held—tentatively in 2005. Four vice presidents were to be appointed two representing major militia (RCD, MLC) one for Kabila’s group, and the other one from the main non-militarized domestic opposition group, and a bi-cameral legislature (500 seat National Assembly/lower house, and 120 seat Senate/upper house). The members of parliament (both houses), the cabinet (61 ministries/departments) and government commissioners were distributed on a proportional basis agreed to in the AGI between the signatory parties—government, RCD-Goma, MLC and internal/non-armed opposition parties.

Although the AGI had called for ‘free and fair” elections for president and the two houses of the legislature to be held within two years of the agreement, the elections did not take place until July, 2006. There was a significant reduction of violence as all foreign troops were officially withdrawn from the Congo in the year after the accord. However, fighting continued between competing militia and between the Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDC) and militia, as the weakened army tried to re-establish control over the eastern third of the country.

“State Failure” and Wars of Attrition: 2003- 2016

In the years that have passed since the signing of the Global and Inclusive Accord (AGI) in Sun City in 2003, peace has not been restored to eastern Congo—most foreign troops may have been withdrawn, but the regime of Joseph Kabila is still in power, with assistance of FARDC and the UN peace keeping troops (MONUC). There have been on-going battles of attrition between militia groups and the FARDC, and between competing militia groups. The killing and displacement of many people continue unnoticed in most of the world. Moreover, the regime has not been able to address dire social and economic needs in the rest of the country. Indeed, there has been a failure to establish effective governance at the local, provincial or national levels across the country. And, there have been no real efforts at encouraging civic engagement or the democratization of governmental institutions. The Congo is no better off economically, politically or socially than it was in the waning years of the Mobutu regime.

After the AGI, Joseph Kabila and his supporters created a political party, the Parti Pour la Reconstruction et el Développement (PPRD), in order to prepare to compete in the 2006 elections. The AFDL, which brought the Kabila regime to power was a military organization that had been incorporated into the re-formed national army (FARDC).

Although the AGI accords had called for an end to violence, fighting continued unabated, howbeit as a reduced level, in the eastern third of the country. In 2004, in clear violation of the peace accord, Laurent Nkunda, who had been a general in the RCD launched an insurgency, with covert support from Rwanda, under the banner of new group the Congrés National Pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP) in North Kivu, his home province. Nkunda justified the insurgency asserting that the Kabilia regime severely discriminated against the Congolese Tutsi, threatening their very existence.

While it is true that Kabila did not trust the Tutsi leaders, whom he tried to neutralize, there is little evidence that he wanted to dispossess the Congolese Tutsis of their land or citizenship. The CNDP’s motives for the ongoing insurgency was based on demographic realities. CNDP recognized that it had little chance to effectively compete in up-coming elections. The AGI agreement established that in order to participate in a post-election government, as a coalition partner, political parties would have to receive at least five percent of the national vote. The leaders of the now defunct RCD who created the CNDP recognized that they were unlikely to achieve the five percent threshold in the national elections scheduled for 2005, and thus viewed military action against a weak regime with an ineffective national army (AFDL) as the best strategy for maintaining some of their influence in eastern Congo.

It is also important to remember that prior to the AGI accords that the RCD had controlled almost a third of the country. This control provided them with the ability to exploit the very lucrative illicit trade in minerals—that will be discussed in the next section. This provided an economic incentive for the CNDP—that was in reality a makeover of the RCD—to pursue its military insurgency.

With support from Rwanda, and using revenues from the illicit mineral trade, the CNDP was able to mount a formable insurgency that challenged the Kabila regime and was strong enough to successfully fend off attempts by the national army to defeat them. Unfortunately, the effects of the insurgency went beyond stymieing the central government’s effort to gain re-gain control of eastern Congo; thousands innocent civilians were killed, many more were forced to leave their home community, with livelihoods destroyed and the social fabric of many communities decimated.

The CNDP insurgency that began in 2004 lasted past the 2006 elections in spite of attempts of the army and UN forces to defeat and/or contain the resistance. On May 23rd, 2009, Joseph Kabila reached an agreement with Rwanda in which Rwanda agreed to arrest Nkunda and stop supporting the insurgency, in return for permission for Rwandan troops to enter eastern Congo in an attempt to destroy the Interahamwe and remnants of other Hutu militia still operating in the Kivus. Sadly, the end of the CNDP insurgency, as destructive as it was, did not bring an end to the violence in eastern Congo.

The CNDP insurgency was not the only violence in the period leading up to the 2006 elections. In the east there were a wide variety of local militia, none of which were as well armed and organized as the CNDP, but nonetheless actively participated in the ongoing death, destruction and displacement that plagued the region since 1996. Most of these militia had no external backers, but were motivated by local grievances against the central government, or against neighboring communities who were competing for scarce resources including access to land and water for livestock. Many of these militia have been classified by the term Mai-Mai (water-water).

Although the preponderance of violence occurred in the eastern third of the country, the pre and immediate post election period witnessed violence in other parts of the country. Of particular interest was a rebellion in the far west Bas-Congo province where in 2006 the mystical Bundu dia Congo sect (part of the large Kongo ethnic group), which had been active for a number of years, protested the abuses and the Kabila regime—sometimes violently –, demanding self-determination for the province. The army and police responded to the protests with brute force killing over a 1,000 protesters in 2006 and 2007, including 300 members of the sect who protested in downtown Kinshasa.

In 2006 the first democratic elections in the Congo since independence in 1960 took place. The elections took place in phases. The elections for the 500 member National Assembly took place in early July. Nearly 50 political parties took part in this election. The largest two parties were Kabila’s PPRD (Parti Pour la Reconstruction et el Développement) and Jean-Pierre Bemba’s MLC. The results of the election were inconclusive in that the PPRD won a plurality of the votes (22%) and 111 seats, but this was barely a fifth of the members of the new national assembly. The MLC came in second with 13% of the vote, giving them 64 seats. Forty-five other parties won seats in the National Assembly, 29 of which won only one seat each! This reality forced Kabila and the PPRD to seek coalition partners among smaller parties. However, the multiplicity of political parties made it difficult for the National Assembly to operate efficiently and effectively, providing an opportunity for the president to exert the authority of the executive at the expense of the unwieldy legislature.

The first round of presidential elections also took place in July 2006. There were more than twenty candidates on the ballot. Kabila won 44.8% of the popular vote, and Bemba won just over 20% of the vote. The third place finisher polled 13% of the vote; thirteen of the candidates got less than .05% of the popular vote. The Sun City accord had stipulated that if no candidate won 50% of the vote that there would be a run-off between the two top vote getters. The run-off took place in October 2006. Kabila won a substantial victory polling 58% of the popular vote. In December 2006, Kabila was inaugurated as the first democratically elected president in the history of the country since the pre-independence election in 1960, ending the post Sun City accord transition period.

In spite of the euphoria following the 2006 elections, which were generally accepted both domestically and internationally as “free and fair,” the five-year period between the 2006 and 2011 elections did not bring peace, stability, or social and economic development to the Congo. The social, political and economic legacies of the Mobutu years had been followed by a decade of brutal warfare. Corruption and poor governance remained rampant in Congo. As a consequence Congo existed with a mere skeleton of a political system with weak or malfunctioning governmental institutions at the local, provincial and national levels. The once vibrant mineral-based economy had been decimated by the corruption and crony capitalism of the Mobutu era and the civil war. Communication infrastructure had been destroyed or left to decay. Educational and health infrastructure were depleted.

Joseph Kabila and the leaders of the PPRD did not have the experience, training, skills or resources, to deal with the huge political, social and economic issues confronting the country. Consequently, the government went on the defensive. Their policies and actions were not directed at addressing the real issues confronting the country; instead, their actions and policies were directed at maintaining their own political power and personal economic wellbeing. The people in eastern Congo were forced to deal with endemic violence and threats to their security with minimal support from the national army and UN peacekeepers. In the rest of the country, economic survival became a twenty-four hour a day endeavor.

As in the last decades of the Mobutu regime, corruption was an ever-present reality in most of the country. Jason Stearns, who lived in Kinshasa in 2010, reports a popular saying among city residents, “Mobutu used to steal with a fork—at least some crumbs would fall between the cracks, enough to trickle down to the rest of us. But Kabila, he steals with a spoon. He scoops the plate clean, spotless. He doesn’t leave anything for the poor,” (Stearns, pg. 322).

The Sun City accords called for legislative and presidential elections every five years. Kabila and the PPRD were deeply unpopular in 2011 when the next elections were scheduled. Peace had not been restored in eastern Congo. In the rest of the country there was virtually no economic growth, the education and health systems were as dysfunctional as they were in 2006, and corruption was ubiquitous. In spite of these realities, the results of the 2011 election were similar to that of the 2006 elections.

In the presidential poll, eleven candidates contested for the office of president. Kabila won just over 48% of the vote, while veteran opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi won 33% of the vote. In the legislative election the PPRD won only 106 out of the 500 seats, which although nearly twice as many as the seats won by the next nearest party, it was just over one fifth or the total seats in the National Assembly. The PPRD was able to build a coalition of allied parties that gave it a bare majority in the National Assembly.

It was clear to the majority of Congolese and to international observers that the elections were flawed. Kabila and the PPRD were very unpopular and had lost their legitimacy. Their victory was assured only through manipulating the election. This was the conclusion of the highly respected Carter Center and European Union observer teams.

The period between the 2011 elections and the end of 2016 (when this module was written) was a near carbon-copy of the previous five years. There was only limited progress in reducing corruption, implementing meaningful reforms in the political arena, or in stimulating sustained economic development.

The chronic violence that has plagued eastern Congo since 1996 continued to go through a cycle of increased fighting, temporary interventions that lead to a reduction in the violence, followed by renewed violence. This happened in spite of foreign military aid aimed at improving the capacity of the national army and the on-going presence of the United Nations Peace Keeping Force (MONUC), the largest UN peace-keeping operation in the world.

Table 1 (above) lists some of the main armed groups that have been involved in the Congo since 1996. At different points during the past twenty years there have been as many as thirty different militia engaged in the conflict In the most recent post 2011 period the militia fighting in the eastern Congo can be divided into two broad categories: groups that are connected historically to Rwanda (and Uganda) and local, more indigenous militia.

The first group includes the remnants of the Hutu dominated Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) that still remained in North and South Kivu along with related Interahamwe, whose strength has been reduced, but who continue to periodically stage attacks against Tutsi militia or the Congolese army. As we will discuss in the next section, all of the these militia are able to keep themselves armed through their participation in the illegal mineral trade. Indeed, much of the violence perpetuated by militia is no longer political, but is economic in orientation, that is, violence is used to protect their economic interests. However, even as the motives change the impact on the local populations continues to be devastating.

In 2009 as part of the peace accords, Rwanda had withdrawn support for the Congrés National Pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP). With the continued violence in the post 2011 election period, there was a growing anxiety among Congolese Tutsi. As a result of this perceived threat to the Tutsi community in early 2012, a new militia (with surreptitious support from Rwanda) developed in the Kivus to “protect” the Tutsi population. This group called themselves the M-23 Movement (named after the May 23, 2009 accord that had ended CNDP). In its short existence the M-23 insurgency resulted in considerable violence and suffering. It was clear that the M-23 was effective only because of support from Rwanda. Within a year of its beginning operations, African Union and the UN put pressure on Rwanda to cut ties with M-23.

As a result of external pressure, Rwanda and the Congo signed an eleven nation peace accord in February 2013 in which the neighboring nations, plus South Africa which had helped broker the agreement, agreed to cease all support for militia operating in Congo. The most concrete result was that Rwanda stopped support for M-23 movement and actually arrested Bosco Ntaganda, the most notorious M-23 leader, who was eventually turned over to the International Court of Criminal Justice (ICC) to stand trial for war crimes. The agreement also reduced the flow of illegal mineral exports into/through Rwanda and Uganda. As a result, significantly less funds are currently available to armed groups to buy weapons and ammunition that continued to fuel the insurgencies.

The second category of militia were the local armed groups. Many of these Mai-Mai militia were autonomous groups fighting mainly over local issues including access to arable land, water, natural resources, that had been severely disrupted by decades of violence perpetrated by outsiders such as the FDLR/Interahamwe, the RCD, CNDP, and the M-23, as well as by the national army (FARDC).

The most impactful of the local militia were the Front for the Patriotic Resistance in Ituri and the Popular Front for Justice in the Congo. These two splinter groups, which operated in the Ituri district of southern Orientale province, were formed in response to brutalities carried out in their region by the FARDC and FDRL and M-23 (Ituri was a mineral rich district). Their primary objective is to eliminate the violence and natural resource exploitation perpetrated by outside groups.

On the political front, the constitution requires that elections for both the legislature and the president be held every five years. Moreover, it stipulates that a president is limited to two five-year terms. Constitutionally, there should have been a national election by December, 2016 without Joseph Kabila being on the presidential ballot, having served two five year terms as president.

However, beginning early in 2016 Kabila claimed that the political conditions in the Congo were not conducive to holding free and fair elections. He suggested that elections should be postponed for at least a year. This suggestion led to wide-spread protests across the Congo, many of which were met by violent intervention by the police. Moreover, there have been expressions of deep concern from the UN, the European Union, the United States and the African Union. In October 2016, the Supreme Court of the Congo ruled in favor of the government’s contention that elections should be postponed indefinitely. As of the writing of this module (January 2017) no date has been set for next elections. Consequently, Kabila remains in power in spite of the constitution and widespread opposition.

It remains to be seen when elections will be held, whether Kabila will try to push through a constitutional amendment in the National Assembly that will allow him to run for a third term, and how the citizens of the Congo will respond to the on-going political stalemate.

Your Turn

Reflective Essay: The United States has been engaged in the Congo since its independence in 1960. Looking back over the information and analysis provided in this module, write an essay that

- Summarizes the nature of U.S. engagement in the Congo from 1960 until the present day

- Provides an analysis of the political impact of U.S. engagement on the Congo,

- Provides your thoughts on how U.S. policy towards the Congo could change so as to improve the possibility of lasting peace in the region.

Mineral Wealth: Congo’s Curse?

Congo is potentially one of the richest countries in the world based on its tremendous wealth in natural resources: abundant fresh water, arable land, diverse flora and fauna, tremendous energy potential in the form of hydro, solar and wind power, and, most specially minerals. Yet, in 2017 when this module was written, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of the poorest nation-states in the world based on per capita income and on social welfare indices. According to an International Monetary Fund report on the Congo (2015) the DRC, in spite of it great wealth potential, was the only country in the world during the first decade of the 21st century whose per capital Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was less than $1 (US) a day. Moreover, as late as 2012 82% of the total population of the country lived on less than $1.25 (US) a day (the official UN and World Bank extreme poverty datum line).

Unfortunately, the very abundance of natural resources has provided incentives for foreigners and local collaborators since independence in 1960, to create processes and structures for exploiting Congo’s natural wealth that maximized profits for outsiders and their local allies, while contributing little to the welfare of Congolese people or to the social and economic development of the country. In fact, the economic and political structures that have been developed, and that are now deeply rooted, to exploit the county’s vast natural resources have not only failed to improve the lives of citizens and to developed the country, these now solidly embedded structures based on exploitative labor practices, the total disregard for environment consequences, the expropriation of nearly all profits, and in the past decade armed conflict sustained by illegal export of minerals have actually resulted in human rights abuses and a significant decline in the living standards of many Congolese. A strong argument can be made that the country and its citizens are worse off economically (and politically) as a result of the country’s great wealth in nature resources than it would have been if the country were less well-endowed in natural resources.

The life of the average Congolese citizen is worse off than any time in the past 130 years, the socio and economic infrastructure is in near total disrepair, the country’s economy is more underdeveloped than any time since independence in 1960. Indeed, this dire social economic situation is in large part a result of the structures put in place to exploit the country’s natural resources that intentionally maximized benefits for international businesses, starting in the colonial era and continued through the post-colonial period benefiting only the political elite.

In this final section of this activity, we will briefly summarize the history and consequence of colonial and post-colonial processes of using Congo’s rich natural resources, paying special attention to the past two decades.

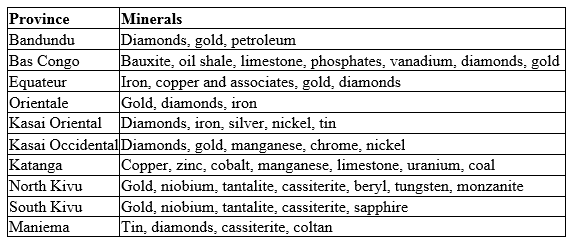

Mineral Endowments by Province

Activity Two: History of the Congo provided details of (i) the brutal exploitation of Congo’s rubber and ivory resources during the era of the Congo Free State (1886 -1908) that resulted in the death and dismemberment of tens of thousands of Congolese while making King Leopold II into one of richest men in the world, and (ii) the less brutal but highly exploitative production system put in place during the era of Belgian colonialism (1908 -1960) that facilitated the massive copper mining operations in Katanga (exemplified by Union Minière) along with a large scale commercial agriculture sector dominated by Belgian settler farmers, commercial enterprises that enriched Belgian businesses, but which did very little to enhance the social and economic infrastructure of the country, and did even less to increase living standards of ordinary Congolese who provided (often unwillingly) the cheap labor that facilitated the colonial economic system.

Earlier in this learning activity we also discussed economic policies and practices as they evolved over the first four decades of the post-colonial period with emphasis on the thirty-year rule of Mobutu Sese Seko. It is important to remember that in 1960 when the Congo became independent, the new Congolese government inherited an economic system that was totally orientated to the exploitation of the country’s vast natural resources, mineral and agriculture for the benefit of international—primarily Belgian owned businesses. During the colonial era, profits from the export of these natural resources were transferred out of the country with very little being spent on the development of social and economic infrastructure. Moreover, the colonial administration intentionally prohibited Congolese from gaining the education (remember, there were less than 50 college graduates in the entire country at independence in 1960), skills and experience necessary to fully participate in management, much less ownership, of commerce. Consequently, the new Congolese leaders were not in a position to challenge the economic status quo at independence. They did not have the capacity to reform the economic system that was designed to benefit international business with no regards to economic advancement of the country or its citizens.

When in the months following independence Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba suggested that substantial economic reforms were necessary for Congo’s development as an independent nation, the Belgians and other Western nations falsely labeled him as a radical socialist under the influence of the Soviet Bloc. More concretely, the Belgians supported the secession of mineral rich Katanga, and along with the CIA engineered Lumumba’s removal from power and his eventual assassination, all within six months of the country’s independence.

As is discussed in detail above, the post-independence period up until the outbreak of the first Great War in 1997 was dominated by the authoritarian rule of Mobutu Sese Seko. The economic legacy of his three-decade rule was just as negative as his political and human rights legacy. His early policy of Authenticité promised meaningful reform of the economic system by (re)turning control of the mines, commercial farms and commercial concerns to Congolese. While there were some efforts in the 1970s to promote Congolese entrepreneurship, in reality, economic Authenticité became a mechanism by which Mobutu secured the support of his political cronies. Authenticité rewarded high- level supporters through transferring ownership of expropriated companies. The majority of the political elite who benefited from this system had no business experience or acumen and had little interest in the day-to-day running of businesses. As a result, Authenticité was an economic disaster for the country. Its most long lasting legacy was the entrenchment of a system of kleptocracy (detailed above) that characterized Congo’s economy from the late 1970s through the demise of the Mobutu regime in 1997.

It is hard to over-estimate the negative economic legacy of Mobutu’s rule. His regime survived politically because of his Cold War importance to the U.S. and her allies and the unquestioned loyalty of security agencies that Mobutu established. Economic survival was dependent on a system that allowed the continued expropriation of Congo’s rich mineral resources by international companies that were allowed to exploit a desperate workforce (whose survival was dependent on their “willingness” work for “starvation” wages). These companies paid virtually no official taxes and were allowed to repatriate huge profits, as long as they underpinned the regime through the direct transfer of funds (“gifts”) into the private accounts of Mobutu and his cronies.

Mining and Natural Resource Management in the Kabila Era:

The initial popular support for Laurent Kabila and the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) who took over political power in the Congo in 1997, was based in large part by the popular hatred of Mobutu who had been forced into exile by AFDL victory. However, this early support of the new regime was also based on the perception that Kabila and the AFDL would institute drastic and substantive economic reforms that would result in a significant improvement of the economic conditions and opportunities of ordinary citizens and lead to substantial local level and national development. Kabila, after all, had promoted himself for decades as a dedicated socialist committed to a people centered economic system that would include, he promised, the nationalization of mines and other major commercial concerns.

However, as detailed in a prior section, once in power, Kabila showed little interest in addressing the massive economic problems facing the Congo. Instead of moving to nationalize the mines as he had promised, he cultivated personal connections with businesspersons from neighboring countries, Europe, Asia (particular China and Israel) and North America, encouraging them to invest in the rejuvenation of the country’s mining industry. Between 1997 when he came to power and 2002 $5 billion worth of mines previously owned by state affiliated companies had been transferred to private international companies with no revenue coming into the state treasury.

Kabila promised potential investors generous economic incentives for their investments, guaranteeing unfettered access to mineral rights, a cheap and compliant labor force (enforced by police and armed forces), and the expropriation of profits with little or no taxation. In return, these businesses were expected to pay generous “licensing fees” directly to Kabila and his top supporters, thus setting into place a “Mobutu 2” type of economic system that paid handsome dividends to the political elite, but did little to improve the lives of ordinary citizens or to promote the development of the national economy.

A 2013 exposé by Africa Confidential provides an excellent synopsis of the symbiotic relationships in an economic system run for the benefit of external business, a few political elite and an unresponsive authoritarian state controlled by those elite. “Exercise of power, from the late Mobutu Sese Seko to the Kabila dynasty, [relied] on access to secret untraceable funds [primarily from mineral deals] to reward supporters, buy elections and run vast patronage networks. . . This parallel state coexists with formal structures and their nominal commitment to transparency and the rule of law. ”

The exploitation of minerals during the Kabila regime (father and son) can be divided into several categories. The World Bank and the IMF (International Monetary Fund) in their reports divide the Congolese mining enterprise into two categories legitimate enterprise and conflict enterprise. The former refers to mining operations (large, medium and small scale) that take place in regions of the country that are under government control and which are supposedly subject to state regulations. The latter category refers to mining activities in the conflict zones in eastern Congo in which the mining, processing and exportation of minerals are not subject to government regulations and in which these processes (mining, processing, export) are controlled by militia that use the proceeds from the sell of minerals to purchase arms that are in the furtherance of their political and economic aims.

It is important to provide a more nuanced presentation and analyses of these processes.

Legitimate mining enterprise can be further divided into sub-categories based on size and ownership:

Large Scale Corporate Mines

Mining in the colonial era was dominated by the Belgian owned Union Minière that was developed to exploit rich copper and cobalt deposits in Katanga province. As reported in our discussion of the colonial history of the Congo, the Katanga copper enterprise resulted in the development of the largest urban wage force (unskilled and semi-skilled) in all of colonial Africa, with the notable exception of South Africa. In the post-independence Mobutu era, copper production steadily declined, partially as a result of the decline in global copper prices, but more importantly, as the consequence Mobutu’s policies that were discussed in great detail earlier in this activity.

In the early years of this century, world copper prices increased fairly substantially, in part as a result of the expansion of the electronics industry, but also as a consequence of the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other regional conflicts in Asia and Africa, which fueled the demand for copper infused weaponry. The Kabila regime, anxious to take advantage of the potential copper windfall, sought to rejuvenate copper production. However, as outlined above, they did not attempt to reform the mining system through greater government involvement, but rather through a more personalized system in which deals were made, most often in secret, that provided international companies with rights to mine copper (and other minerals) with little state oversight, low or no taxes, with no environmental regulation and with the guarantee of compliant low-wage workforce. Most important to international investors, these agreements allowed for the unfettered expropriation of profits. Consequently, just as in the Mobutu era, the average Congolese has received no benefit from the minerals mined and sold on the international market. The low-tax burden on mining companies resulted in limited increases in government revenue that could have been used to develop the social and physical infrastructure essential to the development of the country.

In his 2015 book The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers and the Theft of Africa’s Wealth, British journalist Tom Burgis provides details of how Congo lost billions of dollars in the last two decades as a result of collaboration between the Kabila regime and international business. Much of the “looting” was the result of secret deals that facilitated the illicit transfers of funds out of the country. However, just as devastating were the agreements that allowed the “legal” transfer of untaxed profits out of the country as a result of the deals made by the Kabila regime. It is difficult, due to the secretive nature of these processes to give an accurate estimate of the net outflows of money out of the country. However, according the Burgis’s research, corroborated by the UN and Africa Union 2015 Report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, it is clear that the amount of capital export out of the Congo as a result of both illicit financial outflows and the “legitimate” expatriation of profits far surpasses the combined inflow of capital through foreign direct investment (FDI) and bi and multi-lateral financial aid from developed countries, the IMF and the World Bank. In short, Congo’s vast mineral wealth has been of much greater benefit to internationally owned businesses that it has been to people of the Congo!

Medium Scale “Legitimate” Mining Operations

A small but significant percentage of diamond, gold, and cobalt production in the Congo is undertaken by medium scale mining enterprises. It is worth noting that the Congo has an estimated 70% of the world’s un-mined diamonds; howbeit most of these diamonds are industrial quality that are not worth as much as cosmetic quality diamonds on the world market. Congo currently produces half of the world’s supply of cobalt, an essential component in the production of lithium batteries, which are important in creating modern small electronics such as cell phones. Congo is a fairly minor player in the gold mining industry compared to other major African producers; however, for the last decade an average 850 tons of processed gold was produced in the country.

Medium scale mining concerns, the vast majority of them owned by external individuals or companies, are not as well-known as the companies engaged in large scale mining, most which (the non-Chinese owned) are listed on the major European, East Asian of U.S. based, stock exchanges. The international investors engaged in medium scale mining (some of whom are also heavily implicated in small scale artisanal mining activity, detailed below), are not usually subsidiaries of larger companies, but locally registered companies owned by international business people who were attracted to the Congo by the opportunities to make a fortune.

Dan Gertler, an Israeli diamond merchant, who came to the Congo early in the Kabila regime, is an example of an expatriate businessperson, who, through his close relationship with Joseph Kabila, was able to develop a financial empire based on the control of numerous medium and small scale diamond and gold mines. In less than two decades, Gertler has become a multi-billionaire according to U. N. estimates.

Gertler’s fortune is based not only on controlling mining activity, but was realized through the establishment and control over very secretive and illegal off-shore companies and transactions. His business dealings in the Congo were highlighted in a 2014 report of the Africa Progress Panel, chaired by former Secretary General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan: “A . . . mine owned by the Congolese state or the rights to a virgin deposit are sold, sometimes in complete secrecy, to a company controlled by or linked to Gertler’s offshore network for a price far below what it is worth. Then all or part of that asset is sold at a profit to some of the biggest groups on the London Stock Exchange. . . Gertler did not invent complexity in mining deals. Webs of subsidiaries and offshore holdings are common in resource industries. . . But even by the industry’s bewildering standards, the structure of Gertler’s Congo deals is labyrinthine. ”

This system greatly enriched an international businessperson, while providing substantive financial support that enabled the increasingly un-democratic Kabila regime. Funds that were used both to bolster the regime’s hold on power, but also substantially increased the personal fortune of Kabila (much of it held in off-shore international accounts). However, the system severely disadvantaged the miners who mined and processed the minerals, added very minimally to the government revenue, and strengthened the economic structures that perpetuated the under-development of the country.

Small Scale “Legitimate” Mining

A significant percentage of gold, diamond, and cobalt mining in the Congo takes place in small-scale artisanal mines, involving a small labor force that is too often comprised of adolescents under the age of sixteen. Although much of the conflict minerals (discussed below) are also mined in small scale artisan mines, outside the conflict zones these operations are considered to be legitimate businesses, even where and when child labor is used and the where miners, regardless of age, work under incredibly unsafe working condition and are at times exposed to toxic chemicals. Artisanal gold miners with no protective gear, for example, are exposed to mercury used for processing gold, often resulting in serous skin and respiratory illnesses, at times blindness, and even death.

A 2008 World Bank report on mining in the Congo, provided the following description of a day in the life of typical artisanal miner.

The work day starts early at the artisanal mining camp; sometimes it continues for 12-14 hours a

day, seven days a week. The miner may be from a local village (with or without his family members)

who digs on a seasonal basis as a source of supplemental income. Or, the artisan may be from

outside the vicinity, often an itinerant young man out to strike it rich. In the diamond sector,

teachers, government officials, and army personnel are also artisanal miners. When the miner

arrives on site he will find a plethora of problems. Safety procedures and equipment are either nonexistent

or not used. The work is extremely arduous and often dangerous; numerous deaths occur

in mine shafts due to cave-ins or suffocation. Proper hygiene and sanitary facilities and practices

do not exist. In many cases, the artisanal miner must bring his children onto the mining site

because they have nowhere else (e. g. , school) to go and because an extra pair of small hands are

especially good at getting into small crevasses. Work at the site is highly specialized, with diggers

(men), carriers, crushers, and washers (mostly women and children). Sometimes, especially in the

heterogenite artisanal mines, the digger is a day worker employed by a company, many times in

violation of the labor laws. The digger will work in a team of 5 or 6 others to open a shaft or pit to

expose the ore-bearing strata. There is a significant risk that the ore-bearing strata may not be

encountered, in which case the digger team will have wasted its time and energy. Oftentimes,

government officials arrive at the mine site to extract payments or product in kind from the miners.

In the eastern part of the country, in particular, militias or regular army units are on site to extract

their payments, and officers are alleged to be principal middlemen in clandestine export of the

product to Uganda, Rwanda, or Burundi. Thus, the sales price of the product upon which the

miners’ livelihood depends must be high enough to support the numerous payments and “tolls” at

the border, which exceed those authorized by the law. (World Bank report, p 68, 2008)

Financing of artisanal mining operations in the Congo is complex but reasonably straightforward. More than half of the artisans in the diamond sector are financed by various négociants (regional diamond buyers, traders, and brokers) who in turn are often dependent on even bigger national level mining brokers, such as Dan Gertler. The other half are self-funded using their own money or they will raise the necessary funds to start up the artisan mine through pooling resources from a number of local individuals or in association with négociants.

The excavation necessary to reach the diamond bearing gravel layers or mineral ore can take several days or even weeks. During this start-up period the miners need sustenance and basic equipment, which are often provided up-front by the négociants. Thus, the négociants provide the risk capital necessary for the process, not unlike industrial-scale operations, where mining houses and their financiers provide risk capital for exploration and development. As compensation for this funding, the négociant will typically require in-kind payment of 50 percent of the production. Additionally, the négociant will purchase from the artisans the diamonds, gold or other mineral ore they extract from the artisan miners’ share of the minerals. However, since the price paid to the artisans is fixed by the négociant, the artisans have no way of knowing the value of the diamonds, gold ore that they mined. Consequently, artisan miners in the Congo earn on average US $800-1,000 a year. Négociants and their business partners (foreign and Congolese) who control the export of the gold, diamonds and other mineral mined in small-scale mines, on the other hand, reap a significant profit.

Since there is virtually no government regulation or oversight of these small scale artisanal mines, little to no tax revenues are generated by these mining operations. This has resulted in the normalization of a production and marketing system in which the local artisan labor force is exploited and subjugated to dangerous working conditions that can result in permanent injury or even death. The wages earned by the artisan workers average just over $2 a day, which is not sufficient to maintain basic subsistence for the miners and their dependent family members. Moreover, since there is no tax revenue, none of the proceeds from the mining operations are used in social investments in the local community: schools, clinics/hospitals, potable water, sanitation, road and communication infrastructure, environmental cleanup and restoration from mining activities.

Consequently, a strong argument can be made that not only are the miners, their families and local communities in which the mines are located not better off socially and economically as a result of the mining activities, they are often, on balance, worse off than they would have been without the mining activity.

View Amnesty International video: Amnesty Video (8 minutes) “This is what we die for” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7x4ASxHIrEA and the British produced exposé child labor in “legitimate” cobalt that provide a brief, but powerful, overview of artisan cobalt mine in the Congo & the British produced exposé child labor in “legitimate” cobalt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JcJ8me22NVs

You might find it interesting to read the more detailed written report, “This is What we Die For”: Human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr62/3183/2016/en/

Small & Medium Scale Mining in Conflict Zones: Conflict Minerals

Much of learning activity three and four have focused on the conflict in eastern Congo and the incalculable human suffering and tremendous damage to the social and physical infrastructure of the region. Consequently, there is no need to review this material. However, it is important to highlight the central role that conflict minerals have played in funding and prolonging conflict in region.

The provinces of North and South Kivu, Orientale, Maniema and the northern sector of Katanga are, like the rest of the country, rich in minerals, particularly in Tantalum (a rare earth mineral), the base mineral of Coltan (an essential component of all smart phones and computers), tin, tungsten and some gold, diamonds, nickel and chrome. As a result of the endemic conflict that has inflicted this area over the last two decades, it is virtually impossible for large-scale industrial mining to occur. Consequently, the vast majority of mining that takes place in the eastern Congo, is small-scale artisan mining. However, there is a major difference between artisanal mining in this region and that which takes place in other regions of the country: in eastern Congo artisanal mines are not controlled by local miners or négociants, rather the vast majority of the mines are controlled by armed militia, who use the proceeds from the sale of minerals to purchase arms and to enrich themselves. Most of the labor is forced, with wages, when paid, even less than the $2 a day earned by artisan miners in the non-conflict zones. Workers, often children, are forced to work for long hours in often hazardous conditions with compensation to workers for injuries, exposure to toxic chemicals, or accidental death.

A particularly horrific consequence of the production chain of conflict minerals in the eastern Congo has been the use of rape and other forms of extreme gender violence that is used by the militia as a method of exerting control over local communities. The Guardian newspaper for the United Kingdom produced a short six-minute video “Congo, Blood, Gold and Mobile Phones” that documents the rationale for and devastating consequences of the use of extreme sexual violence as a mechanism control. This video covers this important issue more succinctly and powerfully than a written description. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gGuG0Ios8ZA

It is easy and justifiable to be very critical of the armed militia who have for the past two decades controlled the entire chain of mining production from extracting the minerals, preparing the minerals for sale, through the export of the minerals mostly though the neighboring countries of Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda where the minerals are “re-exported” as products of these countries. However, it is essential to recognize the complicity of other major actors in the sale and use of conflict minerals from the eastern Congo.

Neighboring countries that have benefitted from the re-export of the minerals are complicit in the suffering, violence and destruction of the social, political and economic fabric of the region. Indeed, it is important to recognize the role played by Rwanda and Uganda in particular, in the destabilizing the eastern Congo through their invasion of the area and their decade-long sponsorship of local militia.

Just as importantly, it is essential to investigate the role of international corporations, including mining companies and major cell phone and computer companies that have benefited from the continuous supply from the eastern Congo of Coltan, Tungsten, Tin and Gold, minerals essential to the manufacture of smart phones and personal computers. Until recently when faced with pressure from international advocacy groups, companies like Apple, Google and Samsung (among others) have ignored the fact that the use of conflict minerals supports a deeply violent and exploitative mineral production train.

Yet, these facts beg the questions: are consumers of smart phones and personal computers in Asia, Europe and the Americas also complicit and responsible for the suffering caused by this production system?; and, what responsibility do governments of the U.S. , European, and Asian countries where the international mining and electronic companies are headquartered have regulating the use of conflict minerals?

Related to the second question a small Coded Sal to the 848 page 2010 Dodd-Frank Act that primary addressed regulation of the financial industry in the U.S. following the 2008 economic crisis stated –“it is the sense of Congress that the exploitation and trade of conflict minerals originating in the Congo is helping finance conflict characterized by extreme levels of violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. ” All U.S. registered companies using coltan and other resources from the eastern Congo had to submit a report on their supply chain that was verified by independent auditors. This was a positive Good—but only caused the middlemen to seek other buyers—primarily from Asia and European countries that did not have similar legislation. An unintended consequence of the Todd-Frank regulation was that U.S. based electronic companies moved even more of their manufacturing activities to international subsidiaries primarily in China or east and south east Asian countries that were not subject to the Todd-Frank regulations.

However, companies such as Apple (I-Phone) and Google (Android) would be responsive to protests from consumers in the U.S. and Europe for selling phones that contain components made with conflict minerals for the Congo. There is precedent for such action: violent militia groups in the Liberian and Sierra Leone used the proceeds from trade of blood diamonds to purchase weapons. International advocacy groups pressured international diamond buyers accept the Kimberly Process that put into place a fail-safe system of certifying that all diamonds sold on international market were conflict free diamonds. A similar process could be put in place to certify that all minerals used in the manufacturing of smart phones, laptops and other handheld devices are conflict free.

A number of international advocacy groups have produced both written reports and short videos that highlight the devastation caused by the production chain of conflict minerals in the eastern Congo and which highlight the international connections that support these processes. One such video produced by the Enough Project, “Conflict Mineral 101” is instructive as well as challenging for viewers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aF-sJgcoY20&feature=player_embedded

Your Turn

The aim of this activity to produce a public awareness advocacy plan that (i) informs the U.S. public of role of conflict minerals in on-going conflict in the eastern Congo, (ii) articulates a concrete plan for tracing the use of conflict minerals in smart-phones, handheld electronic devices, and laptops (similar to the Kimberly Process and blood diamonds), and (iii) effectively lobbies (a) major companies like Apple and Google (among many others) to implement a commitment to use only minerals that are certified to be conflict free in their manufacturing of smart phones, etc., and (b) the U.S. government to establish regulations that would make it difficult to market devices in the U.S. , no matter where they are manufactured, that are not certified as conflict free.

As you develop your plans and strategies you may find it helpful to consult the websites of international advocacy group such as Global Witness, The Enough Project, Project Hope, and Amnesty International and UN agencies such as UNICEF all of which have done extensive work on impact of Conflict Minerals on the eastern Congo.

Go on to Activity Five or select from one of the other activities:

- Introduction

- Activity One: Introducing the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Activity Two: History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Activity Three: Postcolonial Congo -Bitter Harvest: Foreign Intervention, Authoritarianism, & Kleptocracy

- Activity Four: Postcolonial Congo -A Country and Region at War

- Activity Five: Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: Framing the Way the West Understood and Thought about Africa and Africans