History of Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe became an independent country on April 18, 1980 CE. For the previous 90 years Zimbabwe, governed by Europeans was known as Southern Rhodesia (1890-1965), and Rhodesia (1965-1980). However, the area which is now called Zimbabwe has a rich human history that dates back many thousands of years. Archaeological records clearly show that people lived in Zimbabwe since approximately 25,000 BCE.

Earliest Human Societies (25,000 BCE – 500 CE)

The earliest known inhabitants of Zimbabwe were ancestors of the Khoi-San peoples who still live in parts of Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. Indeed, archaeological evidence suggests that the Khoi-San peoples lived in parts eastern and southern Africa as long ago as 50,000 BCE. This period in the human history of southern Africa which continues until approximately 100 BCE is known as the Stone Age. Do you remember why this term is used?

The earliest inhabitants of Zimbabwe were hunters and gathers. All of the food they consumed, and the tools and shelter they made, came from the animals they hunted, plants (seeds, fruit, eatable roots) that they gathered, and natural resources provided by their immediate environment—trees, grass, rocks, etc. These early inhabitants of southern Africa lived in small groups that often moved from place to place. Hunting and gathering requires frequent migration from one location to another in search of fresh supplies of food Living in small groups is ideal for migratory hunting and gathering.

Much of what we know about the early peoples in Zimbabwe comes from our knowledge of the contemporary Khoi-San peoples in southern Africa. However, these early inhabitants of Zimbabwe also left important archaeological artifacts. Among these artifacts are stone tools and weapons and marvelous paintings which can be found on cave walls and in rock shelters throughout Zimbabwe and southern Africa

Carefully look at the accompanying photos of paintings made thousands of years ago by the early human inhabitants of southern Africa. What is represented in these paintings? Why do think that animals are so prominent in Khoi-San cave paintings? What can these paintings tell us about the life of these early southern Africans? What are the people represented in the third photo doing?

Archaeologists and historians believe that cave paintings by the early Khoi-San represent the importance of animals and hunting to the early southern Africans. Note how realistic the representations of animals are, while the representations of human hunters are more abstract Dancing is a common representation in cave paintings. Experts believe that dance had ceremonial importance in preparing hunters for the hunt.

The ancestors of the Khoi-San peoples continued to live in what is today Zimbabwe up until approximately 1000 CE. After living in this area for approximately 25,000 years, why did they move away? The answer lies in the arrival approximately 2000 years ago of new groups of people migrating from north of the Zambezi River.

Bantu Migrations, Societies and Kingdoms (0 CE – 1800 CE)

Archaeological evidence suggests that approximately 2000 years ago new groups of people began to arrive in Zimbabwe from the north Although numerous groups of people migrated into Zimbabwe from the north over a period of 1500 years, these migrations are often lumped together and referred to as the Bantu Migrations. Today, over 100 million people comprising many different language and ethnic groups in Central, East and Southern Africa historically belong to the Congo-Niger (Bantu) language group which originated, historians think, in west-central Africa (current day Cameroon, Central African Republic and the Congo.) Early in the last century scholars who studied these migrations referred to the larger language group as Bantu speakers, since ‘ntu was the shared word for a person (Muntu: person; Bantu: people).

Map Eight shows these migrations to the east and south from the original home of the Bantu, or Congo-Niger peoples in West Africa. You can refresh your knowledge of the Bantu Migrations by linking to Module Six: African Geography, Activity Five: Movements.

The Bantu-speaking migrants were significantly different from the original inhabitants of southern Africa. The most significant difference between the new arrivals and the original people of Zimbabwe had to do with four important skills that the new-arrivals brought with them:

*** domestication of animals

*** cultivation of crops

*** smelting and making tools and weapons from iron and other metals

*** pottery (particularly the making of pots)

Why were these skills so important? How did they impact the way of life and history of the peoples who lived in Zimbabwe at this time? Let us answer these questions by looking at each of these skills one at a time.

Domestication of animals. The earliest Bantu-speaking migrants knew how to domesticate and raise animals. As they migrated southwards they brought with them chickens, sheep, goats and dogs Around 1000 CE a later group of Bantu speaking migrants introduced domesticated cattle. Make a list of benefits that you think domesticated animals provided these new societies that moved into southern Africa?

You can refresh your knowledge (and view pictures) of the importance of herding in African societies by linking to Module Nine: African Economies, Activity Two: Food Production.

Cultivation of Crops: The early Bantu-Speaking migrants had the skill of cultivation. Archaeological evidence suggest that the earliest migrants brought with them seed and root crops, the most important being millet, cassava, and sorghum For a description and photos of these crops link to Module Nine: African Economies, Activity Two: Food Production. Upon arrival in southern Africa they were able to “domesticate” local varieties of wild fruits and vegetables

Make a list of benefits that you think cultivated plants provided these new societies that moved into southern Africa.

Iron smelting: Another very important skill that the early migrants brought with them was the ability to mine, smelt, and make tools and weapons out of iron and other metals To refresh your knowledge on the importance of iron smelting to African societies link to Module Nine: African Economies, Activity Three: Case Study of Economic Diversity.

Make a list of benefits that you think iron smelting provide these new societies that moved into southern Africa.

Pottery: Pottery, most specifically the ability to make durable, fire-treated, pots was an important skill that the early Bantu-speaking migrants brought with them as they moved into southern Africa. Unlike the other three skills listed above, the benefits of pot-making may not be as evident. But, think. What may be the benefits of pottery to people and societies?

In combination, these skills provided the new-comers with the ability to prosper and grow as communities in the southern African environment. Agriculture and iron-working allowed the Bantu-speaking migrants to produce sufficient food to become stationary—to stay in one place. Moreover, unlike hunting and gathering societies, agricultural communities were not restricted to small groups; the size of a group was primarily dependent on the amount of food the community could produce.

As will be described below, larger stable agricultural communities developed into important kingdoms that flourished in Zimbabwe between the 12th and 19th centuries CE. Historians refer to this process as political centralization or the development of centralized kingdoms.

In telling this story it is important to remember that while the environment of this area was generally hospitable to farming communities, the region has a history of un-reliable rainfall. Throughout the past two millennia periodic droughts, sometimes lasting for three or four years, have caused great devastation, including the weakening of strong kingdoms.

The growing numbers and spread of Bantu speaking communities throughout the area between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers had a devastating consequence on the indigenous hunting and gathering peoples of this area. The two groups were able to co-exist for some time, but by the sixth century CE, approximately 500 years after the arrival of the first Bantu speaking migrants, competition for land and water sources became so great that the less well organized and more poorly armed hunter and gathering groups were forced to move to the semi-arid and arid locations to the south west, areas that were not attractive to their agriculturalist neighbors (current day Botswana and Namibia). Although small remnants of these communities remained in south west Zimbabwe up until the 19th century, most the hunting and gathering communities had moved out the area by 1000 CE.

The Rise and Fall of Great Zimbabwe

By the 10th century CE much of the high and middle veldt area between the Zambezi River in the north and the Limpopo River in the south was occupied by agriculturalist communities that had moved into Zimbabwe as part of the on-going Bantu migrations. These communities prospered grew on the fertile and relatively well-watered high-veldt areas.

This environment was supportive of the development of larger communities that led, as mentioned above, to a process of political centralization or kingdom building.

The changing social and political environment in Zimbabwe also facilitated economic specialization and diversification. Remember, the early farming communities were subsistence communities This meant that each farming family in a normal year produced only enough food for their own subsistence or survival throughout the year—including stored food for the dry season. However, by the 10th century CE the farming communities, making use of the supportive physical environment, and their on-going development of new skills, were able to produce agricultural surpluses—that is, more than they needed for their own subsistence. As we detail in Module Nine: African Economies, Activity Two Economic Specialization and Diversification, the ability to produce a surplus of food on a regular basis allows and supports the development of specialized occupations that are not related to food production. These new specialized jobs or occupations often enriched the community and may facilitate the process of political centralization.

How so? Two quick examples. The production of surplus food freed up farmers who had good skills as metal-smiths to become full-time metal-smiths. They no longer had to spend time growing their own food since their communities were producing a surplus of food that they could obtain through exchanging iron tools for food. The ability to work full time at iron-smithing provided more time for improving skills that resulted in both better quality tools and weapons and a more abundant supply of iron implements. In turn, this resulted in larger and stronger communities and the need for rules to regulate behavior and individuals in authority to enforce rules and maintain order.

A second example. The production of surplus food and the ability, for example to produce good quality iron implements, provided communities with items that they could trade (exchange) with other communities for goods that they may not have. There is significant archaeological evidence that suggests that as early as the 10th century CE agriculturalist communities in Zimbabwe were exchanging food and iron products with other communities that may not have had access to iron ore, but who lived near salt pans. They exchanged salt—a necessity—for iron tools or food items that they could not produce. The development of trade supported the development of political systems that were necessary for orderly and safe trade, while at same time trade helped new rulers become more important and powerful as a result of their control of the trade between communities.

Great Zimbabwe, which developed in the 12th century CE, was the earliest of the centralized states to develop in all of southern Africa.

To help you understand how impressive the royal center of Great Zimbabwe was, which by the 14th century had approximately 12,000 inhabitants, we have included additional photographs of royal center of Great Zimbabwe as it is today.

When the first European settlers visited the stone remains of Great Zimbabwe (now referred to as the Monuments of Great Zimbabwe) in the 1890s, they were so impressed by its grandeur that they believed that Zimbabwean Africans were not responsible for building the structures Instead they speculated that monuments of Great Zimbabwe were built by non-Africans, perhaps Arab or Asian traders who traveled from the Indian Ocean coast of Mozambique. Why did they take this perspective?

The vast majority of the early European settlers in Zimbabwe held racist views. They believed that African people were intellectually inferior to Europeans, and that African societies and cultures were not capable of developing structures such as those found at Great Zimbabwe. Indeed, had the Europeans accepted, as we now know, that Great Zimbabwe was indeed built by Zimbabweans they would not have been able to view Zimbabweans and their culture and society as inferior. Recognizing the sophistication of African societies and cultures would have challenged the very basis of colonial rule, which Europeans justified on the erroneous argument that inferior African societies and cultures needed European colonial rule to foster development and civilization.

Great Zimbabwe, at the height of its power governed only about a quarter of contemporary Zimbabwe. However, the grandeur of Great Zimbabwe provided an important symbol of African achievement for Zimbabweans during colonial rule. Consequently, it is not surprising that during the independence struggle in the 1960s and 1970s Africans began to identify themselves as Zimbabweans and their country as Zimbabwe.

The Great Zimbabwe. Aerial view of Enclosure/Great Zimbabwe Hill structure/Great Zimbabwe

Wall of Enclosure/Great Zimbabwe Conical Tower

Gateway to Enclosure/Great Zimbabwe Parallel Passage/Enclosure

Historians of Zimbabwe are not exactly sure why Great Zimbabwe declined in importance in the 15th century CE. Archaeological evidence suggests that the royal enclosure at Great Zimbabwe was no longer inhabited by the beginning of the 16th century CE. There is no evidence that Great Zimbabwe was attacked by another emerging kingdom. Rather, historians believe that the environment was a primary factor in the decline of Great Zimbabwe. We know that the soils in the area around great Zimbabwe are not very fertile. Historians believe that several centuries of continuous cultivation depleted the soils of their nature nutrients so that the land could no longer produce the food necessary to support a metropolitan area of 12,000 people

Shona States and Kingdoms, 1400-1900

The significant agricultural, economic, architectural, social, and political skills demonstrated in success of Great Zimbabwe did not disappear with the decline of Great Zimbabwe. Over the next 400 years (15th through early 19th centuries) a number of important kingdoms developed in the area which is today Zimbabwe. These kingdoms are sometimes referred to as the Shona kingdoms because the agricultural peoples who lived in the area between the Zambezi and the Limpopo Rivers spoke closely related languages that belonged to the siShona language family, the first language of approximately 70% of Zimbabweans today.

Map Nine locates three of the most important of these Shona kingdoms, the Torwa state in south western Zimbabwe (height of its power was in the 15th century); the kingdoms of the Mutapa’s –sometimes referred to as Mwenemutapa (17th -18th centuries), the Changamiri’s Rosvi kingdom (18th- early 19th centuries). You will note from the map that while these kingdoms were centered in what is today Zimbabwe they spread into what is today Mozambique and Botswana. It is important to remember that prior to European colonialism in the late 19th centuries current countries did not exist. Since, for example, there were no countries of Zimbabwe or Mozambique in the 18th century, the Mutapa’s kingdom did not cross international boundaries.

Each of these kingdoms became strong as a result of ability of their leaders to take advantage of the natural resources (mineral, water, agricultural) of Zimbabwe, and to make use of the considerable agricultural, iron-working, religious, and organizational skills of their people. There was, however, an additional factor that was very important in the development of the Shona kingdoms, and that was trade. One of the primary reasons why the Mutapa and Changarmiri kingdoms became strong was because they were able to control trade with the coastal regions of the Indian Ocean in what is today Mozambique.

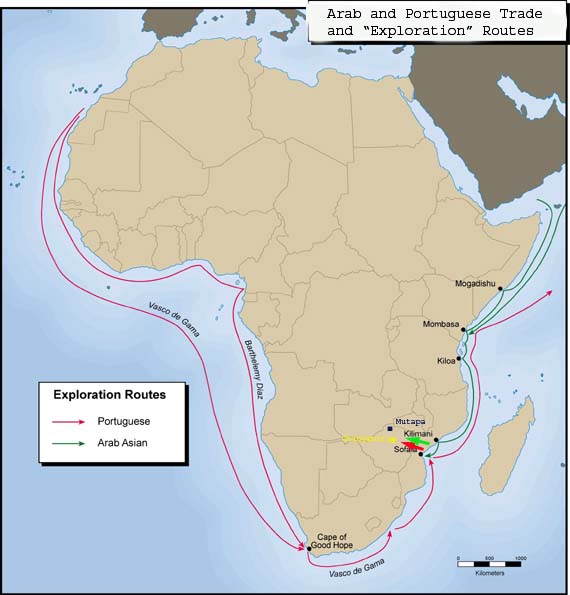

In Module Six: Geography of Africa: Movement we studied the long- distance trade that developed along the east coast of Africa more than 2,000 years ago. The earliest traders to visit the east coast of Africa were from the Arabian Peninsula They brought with them goods from as far away as India and China What were these traders interested in receiving from Africa? Gold and ivory, and after the 16th century the slave trade also became important—just as it was in West Africa at this time (to refresh your knowledge of the West African slave trade link to Module Seven B: History of Africa 1500 to the Present, Activity One: The Atlantic Slave Trade). Gold and ivory were not found along the coast, but in the interior of East and southern Africa Arab traders, who for the most part remained on the coast, recruited local coastal peoples to go into the interior to trade for gold and ivory The most important Indian Ocean Arab trading town near Zimbabwe was Sofala, located along the south central coast of current day Mozambique.

Throughout the interior of eastern and southern Africa there were communities that were able to gain control of the trade with coast. Through the control of the coastal trade these communities or small kingdoms were able to develop into strong and influential kingdoms such as the Mutapa and Changamiri kingdoms of Zimbabwe.

In the early 16th century AD a new group of foreign traders, the Portuguese, appeared on the east coast of Africa, defeating and taking over a number of the Arab coastal trading towns, including Sofala. In Module Seven B we told the story of European contact with Africa in the 15th and 16th century. In telling this story we gave special attention to the development of the Atlantic slave trade. The Portuguese, who were the first Europeans to come in contact with Africa south of the Sahara, along with the Dutch, British, and French, played a central role in the establishing the Atlantic slave trade. However, up until the 19th century the Portuguese were the only European country to show interest in eastern coast of Africa.

Like the Arab traders before them the Portuguese were interested in gold, ivory, and in slaves. As early as 1512 there were Portuguese traders and Roman Catholic priests who came in direct contact with Mutapa’s kingdom in the Zambezi river valley. The Portuguese brought with them a new item for trade, the control of which added significant power to the Shona kingdoms that controlled the trade with the Portuguese. The new item was the gun. Although the Portuguese did not provide the Shona kingdoms with large supplies of guns—they were fearful that the traded guns might one day be used against them!—even a few guns were sufficient to increase the power of the Shona kingdoms, particularly since neighboring peoples had no access to guns.

The kingdom of the Mutapa’s began to decline in the 18th century and that of the Changamiri’s had become quite weak by the early 19th century. Historians believe that there were two main reasons for the collapse of these once powerful Shona kingdoms. The first reason has to do with the decline in gold trade. The Portuguese had never been as interested in ivory as the Arab traders had been, their primary interests were gold and slaves. By the end of the 18th century the easily mined gold deposits in Zimbabwe had been depleted. Consequently, Portuguese traders showed less interest in the high and mid-veldt regions of Zimbabwe, particularly since they were able to obtain slaves by raiding communities that lived nearer to the coast.

The decline in trade with the Portuguese weakened the position of the Mutapas and the Changamiris who had grown powerful through their control of the trade with the Portuguese.

The second reason for the decline in the Shona kingdoms is linked to the first reason. The reduction in wealth within these kingdoms encouraged people once loyal to their leaders to stop paying tribute to these leaders. Moreover, these conditions provided the opportunity for disgruntled chiefs to break away from the larger kingdoms and form their own smaller political communities.

By the beginning of the 19th century, for the first time in nearly 800 years there were no strong Shona kingdoms in the area between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers. It is into this political environment that three new waves of migrations into Zimbabwe took place in the 19th century. Unlike the earlier Bantu migrations that came from the north, this time the migrations come from the south across the Limpopo River. Just as the earlier migrations of agriculturists from the north resulted in very significant changes in the history of Zimbabwe, so too, the new migrations from the south had a tremendous impact on the history of Zimbabwe in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Nguni and Ndebele Migrations: Formation of the Ndebele and Gaza Kingdoms

At the same time that the Shona kingdoms of Zimbabwe were declining in power and influence in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the area south of the Limpopo River, in what is today South Africa, was experiencing the development of a number of strong African kingdoms As presented in much greater detailed in Module Twenty Nine: South Africa, Activity Two: History, the focal point of political centralization and state building in the early 19th century was among the Nguni speaking peoples in what is today the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal. The most powerful of the new states that developed during this period was the Zulu kingdom under the leadership of Shaka Zulu and his successors.

Again, as detailed in Module Twenty Nine, the process of state formation among the Nguni speaking peoples was so rapid and intense that it had significant impact far beyond the coastal regions of KwaZulu-Natal. Consolidation of political power within the Zulu kingdom created a number of disgruntled leaders who lost power and influence to the new Zulu kingdom Instead of accepting defeat, these political and military leaders along with their followers moved away into the interior of southern Africa seeking areas in which they could develop their own kingdoms.

It is important to remember that these Nguni (and Sotho) migrations were not solely caused by the processes of state formation in KwaZulu-Natal. At the same time that the Nguni kingdoms were being formed, Europeans (particularly Afrikaner speaking) were beginning to move out of Cape Colony into the interior of South Africa. This movement of Europeans put considerable pressure on developing African kingdoms whose political well-being was threatened by the arrival of the Europeans. Just as some Nguni and Sotho groups migrated to escape Zulu rule, others moved to avoid defeat or control by the new European arrivals.

The resulting Nguni (and Sotho) migrations were not limited to the interior of South Africa, some groups moved north across the Limpopo and Zambezi River before establishing new kingdoms in areas that today belong to the countries of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, some of which were thousands of miles away from their original homes in South Africa. These Nguni and Sotho kingdom-building migrations, known as the Mfecane (in the isiZulu language) or Difiqane (in siSotho), became a central feature in the 19th century history of most of southern Africa.

As shown on Map Eleven there were two Nguni migrations that had a powerful impact on the area between the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers: the Nguni under Soshangane and the Ndebele (also an Nguni group) under Mzilikazi.

Soshangani’s Gaza Kingdom:

In the early 1820s, Nxaba, one of Shaka Zulu’s generals broke away from Shaka and led his troops north into what is today southern Mozambique, keeping clear of the coastal region which was under the control of the Portuguese. He was able to defeat the local Tsonga peoples In the 1840s Nxaba was overthrown by Soshangane, another Nguni warrior Soshangane established the Gaza kingdom with the aid of his Nguni regiments by the mid-19th century the Gaza kingdom included most of the interior of southern Mozambique and spread westwards into the highland areas of eastern Zimbabwe.

The Shona speaking communities in the 19th century were already politically weak, as we learned above, and were unable to resist incorporation into the Soshangane’s Gaza kingdom. From the eastern highlands regiments of Soshangane’s army made frequent raids for cattle into the neighboring mid-and high-veldt regions of central Zimbabwe. While these areas were not incorporated into the Gaza kingdom, raids from the Nguni soldiers further weakened the Shona political communities in what had been, just a few decades before, the core of Chagamiri’s Rosvi kingdom.

Ndebele Kingdom:

Mzilikazi, like Nxaba, was an important ally of Shaka Zulu who fell into disfavor Instead of accepting humiliation, Mzilikazi gathered the regiments of soldiers who remained loyal to him and in the 1821 moved westwards across the Drakensburg Mountains into the high veldt interior of South Africa, settling in the area north of the Vaal river in what is today the South African provinces of Guateng and Limpopo Mzilikazi’s highly skilled and battle tested regiments were able to defeat the local Tswana and Sotho speaking agricultural communities.

The Ndebele kingdom grew rapidly in the high veldt regions between the Vaal and Limpopo rivers in the late 1820s and early 1830s. Historians believe that the Ndebele kingdom may have developed into the most powerful African kingdom in South Africa. However, just as the Ndebele kingdom was achieving significant power European (Afrikaners) migrations arrived from the south. These communities that had been forced out of Cape colony and who had been stopped by the British in Natal (KwaZulu-Natal) were determined to establish a viable independent Afrikaner nation in the high veldt area north of the Orange and Vaal Rivers.

This resolve brought the Afrikaans speaking migrants into direct conflict with the Ndebele kingdom. The confrontation of Afrikaner and Ndebele interests led to a series of battles in the mid 1830s. At first, even though the Afrikaners were armed with guns, the well trained and more numerous Ndebele soldiers were able to hold their own and on occasions even defeat the newcomers. However, as the Afrikaner community continued to grow with new reinforcements from the south Mzilikazi recognized that he would never be able to stop the encroachment of the Afrikaners. Consequently, in 1836 Mzilikazi made the strategic decision to move his kingdom to the area north of the Limpopo River into what is today south western Zimbabwe, where he believed his kingdom would be out of the reach of the Afrikaner community.

When the Ndebele moved north of the Limpopo they did not face real resistance from the weakened Shona communities in southern Zimbabwe. By the 1850s the Ndebele kingdom was fully established in western Zimbabwe. In this new environment the Ndebele settled into more established way of life than they had experienced in past 30 years. The raising of cattle was central to the Ndebele economy. They also grew crops, but subsidized their grain and vegetable consumption through food received as “tribute” from defeated Shona communities.

The power of the Ndebele kingdom was based on a system of compulsory military service. All young men were forced to serve in age-group regiments for up to period of five years along with other young men of their same age. The age-regiments were charged with the defense of the kingdom, but in addition they were also responsible for increasing the cattle wealth of kingdom through raids on the neighboring Shona and Tswana communities. Sometimes these regiments carried out attacks on Shona communities as far as hundreds of kilometers from the center of the Ndebele kingdom. However, Ndebele raiders seldom if ever reached Shona speaking communities in the north and north-east regions of Zimbabwe.

The Shona communities that were defeated by the Ndebele regiments were often forced into a tributary relationship with the Ndebele community. These communities were not ruled directly by the Ndebele but they were expected to pay regular tribute payments—“taxes”– in the form of cattle, grain, salt, and iron tools, to the Ndebele.

In 1868 Mzilikazi died and was replaced as king by his son Lobengula who continued to govern in the tradition of his father. Over the next two decades the Ndelele kingdom continued to be strong and to dominate western Zimbabwe. However, from the beginning of his reign Lobengula was confronted by new potential threat from the south. By the 1860s Europeans began to arrive in the area north of the Limpopo River. The new arrivals came from two distinct groups: Christian missionaries interested in evangelizing the Ndebele and Shona peoples and mining speculators who were attracted to the area by reports of gold.

For a number of years Lobengula was able to control the influx of European miners and missionaries into the Ndebele kingdom. However, events in South Africa in the 1880s led to an external threat to the Ndebele kingdom that Lobengula and his brave regiments would not be able to resist.

European Colonialism and the Creation of Southern Rhodesia

In the late 19th century there was a second waive of migrants—or second invasion—into Zimbabwe from south of the Limpopo. To an even greater extent this invasion of outsiders was to have a powerful and lasting impact on the peoples and history of Zimbabwe.

The arrival of Europeans in Zimbabwe is closely tied to developments in 19th century South Africa. As is detailed in Module Twenty: Regions, Southern Africa & Module Twenty Nine: South Africa, Activity Two: History, two inter-related trends were of particular importance: the discovery of large deposits of minerals (diamonds and gold), and the creation of new European nation-states within South Africa.

In the 1860s what was up on till then the largest deposit of diamonds in the world was discovered at Kimberly, deep in the interior of Cape Colony, South Africa. Twenty years later, in the 1880s, the world’s largest deposits of gold were discovered on the Witswatersrand (current day Johannesburg) just to the north of the Vaal River. These discoveries resulted in a large influx of European migrants into the interior of South Africa, not dissimilar to the Gold Rush in California following the discovery of gold in the 1840s and 1850s.

Important political developments were taking place in South Africa during the same period. Up until 1800 the European presence in South Africa, while significant in some regions was limited to southern coast regions (Cape Colony) and the isolated pockets of settlement along the east coast (Natal colony). At this time Dutch, and to a lessen extent French protestants –the Huguenots, who moved to South Africa to escape religious persecution in France– made up the European settler communities in South Africa. The Dutch had established their first settlement at Cape Town in 1652 CE.

At first Cape Town was not considered a permanent settlement for the Dutch, rather it was used as a refreshment stop for Dutch ships that carried out the lucrative spice trade between Europe and the Dutch East Indies—current day Malaysia and Indonesia. The settlers at Cape Town were expected to provide fresh supplies of meat, fruit, vegetables and fresh water for the ships on their way to and from the East Indies.

During the next 150 years the Dutch settler community in the Cape grew and slowly began to move into the interior and eastwards along the Cape coast where they lived in isolated communities that had minimal contact with authorities at Cape Town Agriculture was the mainstay of these rural communities. Similar to the American frontier/pioneer communities in 19th Century U.S., the Dutch communities in the Cape enjoyed their freedom from governmental control.

By the end of the 18th century the Dutch communities in the Cape in isolation from Europe had developed their own unique culture and their own language. Their language, which was a combination of Dutch, Malay (adopted from the slaves they imported from Malaysia) and various African languages, became known as Afrikaans. Over time the people began to refer to themselves as Afrikaners—speakers of Afrikaans. Later, in the 19th century, the British who gained control of the Cape referred to the Afrikaners as Boers-the Dutch word for farmers.

In Cape Town and the immediate surrounding districts farms were much larger than they were in the more distant communities. The larger farms required labor. In the 17th century the early Dutch settlers attempted to force the local African communities of Khoi-San peoples to work on their farms were they were treated like slaves. Consequently, in order to escape forced labor many of the Khoi-San peoples who had lived at the Cape for thousands of years moved into the interior to areas outside the control of the Dutch settlers. To meet their labor demands the Dutch began to import slaves from Malaysia (South East Asia) and from the Portuguese in east Africa.

Slavery remained central to the Afrikaner community until the British took control of the Cape in 1806 CE.

The Afrikaner communities were not pleased when the British took control of the Cape. The Afrikaners were used to living with very little government interference. They resented the imposition of the English language and of new rules, most particularly the early British decision to ban the importation of slaves in 1808 and the emancipation (freeing) of slaves in 1834.

Within 20 years of British rule there were Afrikaner communities that were so upset with the British rule that they decided to move away from the British controlled Cape Colony into the interior of South Africa. This migration of Afrikaner communities into the interior which began in the 1830s became known as the Great Trek or Voortrek (People’s Trek).

The majority of the Afrikaner communities remained in Cape Colony, but the Great Trek brought European communities for the first time deep into the interior of South Africa. Gradually over the next decades these migratory Afrikaner communities moved further to the north and into direct conflict with the Nguni, Sotho, and Tswana communities. These African communities actively resisted the encroachment of the Afrikaner, but they had been weakened by the Mfecane/Difiqane. Consequently, in most cases these Nguni, Sotho and Tswana communities eventually came under the political control of the Afrikaner invaders.

In the 1840s the Afrikaner trekking communities attempted to establish two independent states in which Afrikaner communities would govern themselves and the African communities free from British contro.l In the early 1850s two independent Afrikaner states were officially recognized by the British—the Orange Free State (located between the Orange and Vaal Rivers, and the Transvaal Republic (located between the Vaal and Limpopo Rivers), west of the Drakensburg mountains.

The British reluctantly recognized the independence of these two Afrikaner state since they did not have the military capability of monies necessary to bring these republics under British control. The British attitude toward the Afrikaner republics, however, dramatically changed in the 1880s with the discovery of gold in the Transvaal British businessmen located in the Cape very much wanted to gain control of the huge gold mines on the Witswatersrand.

The most important of the British businessmen who had interest in the Transvaal was Cecil Rhodes, a very rich and influential businessman turned politician who had made his millions by gaining control of the Kimberly diamond mines in the 1860s.

Rhodes used his fortune to help him become “chief minister” (head of government) in the Cape Colony in the 1880s. He used this position to help further three goals: he wanted to gain control of the goldfields of the Transvaal for himself and other European businessmen, he wanted make sure that the British and not the Afrikaners gained access to what he believed were vast mineral deposits north of the Limpopo in Zimbabwe, and thirdly, he was great supporter of British colonialism in Africa—he wanted Britain to colonize the entire area form Cape Town in South Africa to Cairo in Egypt, more than 6,000 miles to the north.

Although British business concerns gained control of the gold fields of the Transvaal in the 1880s, the Afrikaner government of was able to resist direct political control by the British until the end of the South African War (also known as the Anglo-Boer War) in 1901.

Similarly, the British government was not able to help fulfill Rhode’s second goal of gaining control of the areas north of the Limpopo River. The British government did not have the funds in the 1880s and 1890s to sponsor an invasion and colonization of Zimbabwe. Rhodes however, was anxious to control the promised wealth of Zimbabwe and to make sure that the Afrikaner government of the Transvaal did not sponsor the colonization of this area. To achieve this aim, Rhodes presented the British government with a proposal.

Rhodes proposed the formation of a commercial company that he would fund—the British South African Company (BSAC) Rhodes requested that the British government provide the BSAC with a royal charter that would give the Company the right to make treaties with African rulers north of the Limpopo on behalf of the British government. These treaties would serve as the basis for the colonization of these areas on behalf of Britain. According to this proposal the BSAC would administer the new colonies on behalf of the British government In return, the BSAC would be given mineral and land rights in the new colonies. That is, all the minerals found would belong to the Company and the Company would have the right to sell and distribute land confiscated from the Ndebele and Shona peoples.

Rhodes persuaded the British government with his scheme. In 1887 the BSAC under the control of Rhodes was granted a royal charter to colonize the areas north of the Limpopo River Rhodes planned to use the BSAC to fulfill three goals—keeping Afrikaners out of the areas north of the Limpopo, incorporating this area into the British Empire, and insuring that he and his business associates would control and have a monopoly of the mineral wealth in the vast regions beyond the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers.

The story of the colonization of Zimbabwe by the BSAC is both sad and intriguing. The Royal charter gave the BSAC permission to make treaties on behalf of the British but not to directly invade and conquer Zimbabwe. To colonize Zimbabwe, under these conditions, the BSAC was forced to engage in deceit, misrepresentations, and outright lies.

From the beginning of the BSAC initiative to gain control of Zimbabwe it engaged in a huge deceit. Rhodes and the agents of the BSAC did not want to have to go through the time consuming and deceptive process of travel throughout the vast area of Zimbabwe encouraging the many Shona communities to sign-away their political and economic rights through treaties with the BSAC.

To forgo this process the BSAC claimed that the vast majority of what is today Zimbabwe was under the effective control of Lobengula and were incorporated into the Ndebele kingdom. This was clearly not the case. While the Ndebele kingdom controlled the south western region of Zimbabwe and had tributary relationships with Shona peoples in adjoining areas, the Ndebele never controlled more than a third of current day Zimbabwe. Why did the BSAC make this claim on behalf of the Ndebele kingdom? If the Company could persuade Lobengula to sign a treaty the BSAC could claim that the treaty covered not only Matabeleland, but all of what is today Zimbabwe Under this plan the BSAC would not have to make treaties with a single Shona community!

To put this plan into action the BSAC first had to persuade Lobengula to sign a treaty with the BSAC. To accomplish this task Rhodes solicited the assistance of Charles Rudd, one of his most trusted associates, and the Rev. John Moffat, a missionary who had occassionally visited with Mzilikazi and Lobengula.

In the late 1880s the Ndebele kingdom was at the height of its power; as such there was no reason for Lobengula to sign a treaty with BSAC—what could they offer in return for signing away the mineral rights in his kingdom? Well, Rudd, on behalf of the BSAC promised Lobengula 1,000 “Martin-Henry Breed rifles, together with one hundred thousand rounds of suitable ammunition.” This offer may have been attractive to Lobengula since the promised rifles and ammunition would strengthen his relationships with all neighboring peoples. As a kind of “signing bonus,” Rudd offered the king, 100 Pounds British Sterling.

We now know from the Rudd’s and Moffat’s diaries that Lobengula was very reluctant to sign a treaty that gave up mineral rights in his territory. Lobengula correctly, as it turned out, feared that such a concession would lead to a large influx of Europeans and eventually to the weakening of the Ndebele kingdom. He remembered the history of the Ndebele peoples when they were forced out of the Transvaal by the advancing Afrikaner communities.

Desperate to have a treaty with Lobengula, Charles Rudd with the knowledge of the Rev. John Moffat, deliberately lied to Lobengula. They indicated that they had written a new treaty which simply affirmed the friendship between the British and the Ndebele. In reality the Rudd Concession, as the treaty became known, included the following statement:

[In return for guns and money, Lobengula gives to the BSAC] complete and exclusive rights over all metals and minerals in my kingdom. . .together with full power to do all things they [the BSAC] deem necessary. . . to procure the same. . .and I undertake to grant no concession of land or mining rights to [anyone else].

It was only several years later that Lobengula realized that he had been deliberately deceived. He appealed to Queen Victoria to revoke the Rudd Concession, but by that time it was already too late, the BSAC had moved the first European settlers into Zimbabwe. Moreover, the Company used the Rudd Concession to justify its invasion of Zimbabwe.

Remember the first deceit? The BSAC claimed that the Rudd Concession covered not only Matabeleland, but all of Zimbabwe, since they claimed that all of the Shona communities were subjects to the Ndebele. The Company then used the phrase in the concession that we highlighted to justify claiming political control over all lands between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers and west of Portuguese Mozambique.

The BSAC falsely argued that the Rudd Concession gave them the mineral rights to all of this area “together with full power to do all things they deem necessary to procure the same.” Clearly, the BSAC argued, the only way that they could guarantee the protection of their miners and the export of minerals was to have political control over this area. Moreover, they argued, the phrase quoted above, gave them the right to take political control of “Southern Rhodesia.”

Map Eleven shows the routes used by the early BSAC European settlers as they moved into Zimbabwe in the early 1890s. Please note that the Company was careful not move settlers into the heart of the Ndebele kingdom. In fact they traveled to the south of the Matebeleland before moving towards the north into the mid and high-veldt regions, heavily populated by Shona communities, where they established a number of settlements. The most important of these BSAC settlements were Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) very near Great Zimbabwe, and Salisbury (now Harare) in the north east, which was to become the capital of the new colony of Southern Rhodesia.

It is important to remember the BSAC was a commercial company, not a government, it did not have an army, it had no citizens to recruit for the invasion of Zimbabwe. How then did the Company find people who were willing to move into Zimbabwe? Gold played a central role in the recruitment of Europeans willing to participate in the BSAC project in Zimbabwe.

Remember that the world’s largest deposits of gold had been discovered in the 1880s on the Witswatersrand, just two hundred miles south of Zimbabwe. This discovery had led to the widely accepted belief that there were similar deposits of gold to be found north of the Limpopo River. When the BSAC announced that it would give significant mining claims in Zimbabwe to any healthy European adult male who would join the BSAC project there were many people who responded to the invitation. These early settlers were not trained soldiers, they were not part of a legally structured army, but they were willing to join the Company project, and to potentially go to battle with resisting Ndebele and Shona communities, just so they could prospect for gold that they believed existed in abundance in Zimbabwe.

After they had established a few settlements among the Shona communities the BSAC was not satisfied with excluding the Ndebele kingdom in their area of potential control. In 1893 the Company provoked an incident with a small regiment of Ndebele soldiers not far from Fort Victoria. The Ndebele responded to the provocation by counter-attacking the Company troops. This counter-attack provided the BSAC with the excuse they needed to carry out a full-scale attack on the Ndebele. Although the Ndebele fought bravely, they were no match for the newly invented machine guns that were used by the Company “volunteer” soldiers Lobengula was killed and the Ndebele surrendered to the BSAC.

“Volunteer” soldiers fighting on behalf of the BSAC were richly rewarded for their efforts. In addition to receiving additional mining claims, they were each given the right to claim up to 10,000 acres of land in Matabeleland, and they were given a share of the Ndebele cattle that the Company confiscated at the end of the war with the Ndebele.

After the defeat of Lobengula, the BSAC began to set up a system for governing the territory that they now called Southern Rhodesia in honor of Cecil Rhodes [By 1900 the BSAC had gained control of the area north of the Zambezi River, current day Zambia, which they called Northern Rhodesia.]. The BSAC was interested in keeping their administration—government—as small as possible Why do you think this was the case? Why not show off the fact that by 1900 the Company controlled an area four times larger than Britain by developing an impressive governmental infrastructure?

Money! The BSAC was a commercial company, and as such they were interested in making money, not spending money on supporting administrative offices of government. In fact, the Company was only willing to spend money in two areas: security and transportation. Making profits depended on the safety of European settlers and their economic activities, particularly mining. The BSAC was willing to spend revenue on developing a Rhodesian police force that could protect their interest from Shona and Ndebele communities that were angry with their loss of land, cattle, and freedom.

A second area in which the BSAC was willing to spend money was on the development of rail transportation. The Company realized that the economic prosperity of Southern Rhodesia was partially dependent on the ability to import goods necessary for commerce and mining and to easily export the abundance of minerals that they anticipated would be found and mined in Southern Rhodesia. As early as 1896, the Company sponsored the extension of a South African rail system into Southern Rhodesia. By 1897 the railroad reached Salisbury. And by 1898 the branch of the Rhodesian railroad was completed between Bulawayo and Victoria Falls on the border with Northern Rhodesia.

The Shona communities of the mid and high veldt were not pleased with the new-comers, but given events in their recent history they were not strong enough to stop the BSAC advancement. In the early years of Company rule Shona were particularly angered by the BSAC demands for labor and to a lesser extent land. Remember, the Company and the European settlers were most interested in finding and mining minerals. Mining is generally an activity that demands hard labor. Where were the Company and settlers going to find workers to carry out the hard tasks of digging for minerals?

To the BSAC the most obvious answer to this question were Shona men. At the very beginning of Company rule they tried to recruit strong able-bodied Shona men to work for them. However, very few Shona were willing to work for the European miners. Should this response have surprised the European settlers? After all, the land of the Shona had been invaded and taken over without any treaties or compensation to the communities that had lived in the area for at least 1,000 years.

Given this situation the BSAC had to come up with a way of getting the inexpensive labor that they needed. Slavery was not an option since the British had abolished slavery in all its colonies in 1837. Given this restriction the Company introduced a system of taxation. The system they set up required the headmen of Shona villages to collect five British shillings for every house in their village. This tax became known a “house tax.”

Why did they decide to base the tax on houses and not on individuals? There was no census, so the BSAC had no way of knowing how many people actually lived in a village. Moreover, they knew that they could not trust the headmen to give them an accurate count, if they had asked the headmen how many people lived in their villages. Can you blame the headmen? Why should they cooperate with the people who had invaded their land? Moreover, they were suspicious of why the Europeans would want to know how many people lived in their village.

The BSAC used the number of houses in a community to estimate how many men there were in the village. They assumed (often wrongly) that there was one adult man for each house in the community.

How did the imposition of the “house tax” deal with the BSAC’s labor problem? Think carefully, the connection between taxes and labor is not complicated. Jot your thoughts down on a piece of paper.

Were the Shona communities pleased with the imposition of the “house tax?” Absolutely not! Remember, how important the issue of “taxes without representation” was in the history of colonial America? In fact, most village head-men refused to collect the tax. The Company responded to this resistance by arresting and jailing the head-men who refused to collect the tax.

The First Chimurenga:

Both the Shona and the Ndebele peoples were upset with the invasion of their lands by the European settlers and their terrible treatment by the BSAC.

The Ndebele were angered by the deceit with which the BSAC had gained control of their kingdom, by the death of Logbengula, the humiliating treatment of many of their chiefs, by the theft of their lands and many of their cattle by the settlers, and by the removal of many Ndebele peoples from what was the central part of the Ndebele kingdom around Bulawayo to more arid native reserves to the north. Then, in early 1896 there was an outbreak of rinderpest, a serious cattle disease, Matabeleland. To keep the disease from spreading the BSAC ordered the killing of all cattle—even the ones not yet infected—in the affected areas.

This action was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Remember, cattle were the core component of the Ndebele economy. To lose the small herds of cattle that remained in their hands was more than the Ndebele were willing to tolerate. In March 1896 armed Ndebele warriors attacked European mining and farming compounds outside of Bulawayo killing a number of settler.s The settlers were surprised by and were certainly not ready for the Ndebele uprising. Consequently, while the BSAC and the settlers were able to eventually contain the Ndebele resisters they were unable to defeat, or to stop the attacks by, the Ndebele warriors.

Cecil Rhodes, afraid that an on-going rebellion would scare off new settlers and other investors, potentially bankrupting the BSAC, traveled to Zimbabwe to meet with the Ndebele Indunas (chiefs). After a series of Indabas, (high level meetings), between Rhodes and Ndebele chiefs, an agreement was reached that ended the rebellion. In the negotiations Rhodes agreed to restore some of the powers of the Ndebele chiefs, to return some of the land and cattle that the BSAC had confiscated from the Ndebeles in 1893, and to allow some of the people who had been forcibly removed to reservations in the arid north to return to their original homes.

Independent from the Ndebele rebellion, but beginning in the same year, 1896, a number of Shona communities in north eastern Zimbabwe systematically attacked European settler communities. The Shona, like the Ndebele had much to be angry about. Their land had been invaded, cattle and crops stolen, increasing numbers were forced off their ancestral farmlands, and, as is detailed above, taxes were imposed on the Shona as way to get them to work under harsh conditions in European mines and on their farms.

Whereas the Ndebele uprising was led by former indunas (chiefs) and age regiments, leadership of the Shona uprising came from Shona spiritual leaders. As in many societies and cultures around the world, religion played an important role in Shona society. A detailed description of indigenous religions in Africa is provided in Module Fourteen: Religion in Africa, Activity Two

In the teachings of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, individuals have a spiritual as well as physical essence, sometimes referred to as the soul. According to these teachings, when the physical body dies the soul of the person continues to live in an afterlife. The Shona, like many Muslims, Christians, and Jews, believe that humans have a spiritual essence that continues to exist after a person has died. According to Shona belief the spiritual essence of those who die, often referred to as the ancestors, continue to have an active interest in the welfare of their families and communities.

One of the central functions of religious leaders in traditional Shona culture was to be a voice for the concerns of the ancestors. Some religious leaders became mediums through which important ancestors could voice their concerns about the communities that they left behind. In 1896-1897, two of the most important Shona religious mediums, Nehanda and Kaguvi, spread a message that the ancestors were very unhappy with actions of the European settlers and the BSAC. These priests actively encouraged the people rise up against the invaders.

Given the ill treatment of the Shona peoples and the high regard in which Nehanda and Kaguvi, were held by the people, their message was readily received in many Shona communities.

The Shona up-rising, called the Chimurenga (uprising in Shona) lasted longer and was more destructive of human life and property than the Ndebele uprising. The length and intensity of the Shona uprising reflected the strong opposition of the people to European rule. Moreover, it also reflected a different attitude on the part of the BSAC. Whereas Rhodes, and settlers, had been willing to negotiate a settlement with the Ndebele, they were not willing to negotiate with the Shona. Their policy was to completely suppress and destroy Shona resistance. Consequently, the uprising lasted until late 1897 when the two central Shona priests were captured and executed In the process of suppressing the uprising, many Shona were killed.

Although they were not successful in driving out the BSAC and the European settlers, the Ndebele and Shona Chimurengas demonstrated that the people of Zimbabwe were strongly opposed to outside rule and that they were willing to take up arms to demonstrate their desire to regain control over their land, cattle, ways of living and political institutions. The brave struggle of the Chimurenga provided inspiration for Zimbabwean nationalists 70 years later when they took up arms to fight for their freedom in what the nationalists referred to as the Second Chimurenga.

Rhodesia under European Control 1897-1980

By 1900, having brutally suppressed Zimbabwean attempts of resistance, the BSAC had established effective control over Southern Rhodesia. However, Company rule lasted only until 1923 when it gave control of the government to representatives of the European settler community. Why did the BSAC after its struggle to gain control over Zimbabwe, voluntarily give up political control less than three decades in power? The primary reason, once again, has to do with money!

Do you remember the main reason why a commercial company was interested in gaining control over and governing Zimbabwe? That’s correct Cecil Rhodes and the stockholders of the BSAC had believed in the 1890s that the area between the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers was rich in minerals—particularly gold—just like the Witswatersrand region of South Africa where huge deposits of gold had been discovered a decade earlier in 1884.

The share-holders and administrators of the BSAC through their deceitful negotiations with Lobengula claimed the rights to all minerals in Zimbabwe. Had Zimbabwe turned out to be rich in gold and other minerals, the BSAC would have become a tremendously wealthy company. However, Zimbabwe did not have the mineral resources that the Company had anticipated. Consequently, not only did the company fail to generate much revenue, the administration of Southern Rhodesia was expensive. In fact, the BSAC was forced to spend more money on governing than it earned in commercial profits. Consequently, by 1920 the BSAC stockholders were willing and ready to give up their governing responsibilities.

By the 1920s it was not just the BSAC that unhappy with Company rule. The European settler community in Southern Rhodesia had come dislike the BSAC Why? Again the answer has to do with money! The slowly growing settler community strongly felt that they needed the government to develop the transportation and communications infrastructure of the country and to provide financial support to the settler agricultural, commerce and mining initiatives. Without this support, European settlers struggled to survive. However, the BSAC, given its financial condition was unable and unwilling to provide the economic support that the settler community demanded.

The Zimbabwean African communities were, of course, also very unhappy with Company rule, but neither the BSAC or the European settlers cared about concerns of Africans. Africans were not invited to participate in the debates about the future of Southern Rhodesia.

In 1923 the British Colonial Office in London negotiated an agreement with the BSAC and representatives of the European settler community regarding the future governing of Southern Rhodesia. According to this agreement a referendum would be held in 1924 in which the European settlers (not the Africans who were in the vast majority of the population) would be given a choice on how they would be governed.

The choice was this: they could vote to be incorporated into the Republic of South Africa, or they would be given the status “responsible governance.” Responsible governance would mean that the settlers would be able to elect representatives who would have the responsibility to make and administer laws that would govern Southern Rhodesia. This was almost like independence, but not quite. All laws passed were to be subject to the veto of the Colonial Office in Britain which would also develop and maintain control of the Southern Rhodesian army.

How did the European settlers vote in this referendum? They overwhelmingly voted in favor of “responsible government.” In 1924, the European settlers, with a population of less than 15,000, very few who had been born in Zimbabwe, took control of Rhodesia, with no political voice given to the more than 700,000 indigenous Zimbabweans!

Based on what you have learnt so far, what do you think was the top priority of the new European settler dominated government of Southern Rhodesia? The top priority of the new government was to establish political and economic policies and institutions that would solidify and maintain complete European settler control of South Rhodesia while increasing the prosperity of South Rhodesia.

On the political front the new regime immediately passed legislation that guaranteed European settler control of the newly established government. To begin with Africans, although they outnumbered the European settlers by a ratio of greater than 60 to one, were denied the franchise (the right to vote), effectively excluding Zimbabweans from participating in any aspect of the government of Southern Rhodesia Membership of the Legislative Assembly (parliament) which debated and passed laws governing the country, was exclusively European. The Chief Minister (prime minister) and the cabinet, who governed the country, were also exclusively European, as were members of the judiciary (judges) whom interpreted and enforced the laws of the country.

By granting European settlers a monopoly control over the political system, “Responsible Government” guaranteed that the social and economic, as well as political, interests of the settlers would also be realized.

On the social front the Legislative Assembly passed a series of laws that established de jure segregation of the races. For example, as in South Africa, black Zimbabweans were not allowed to live in or even enter (unless they were needed as workers) areas set aside for Europeans Legislation established (as will be detailed in the next activity). Native Reserves, similar to Native American reservations in the United States, where black Zimbabwean were forced to live. In addition, schools, hospitals and social amenities (restaurants, hotels, movie theaters, etc) were segregated by race. Europeans did not want to interact with black Zimbabweans, except where they were needed as workers on farms, in mines, or in growing urban areas.

On the economic front the Legislative Assembly passed a number of laws that were aimed at assisting European business while making it impossible for black Zimbabweans to compete with the European settlers. In the next activity we will detail the land crisis in contemporary Zimbabwe. The roots of this crisis are in the land policies established by the Southern Rhodesian settler government.

Remember that in the 1890s European settlers were attracted to the area between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers because they believed that they would become fantastically wealthy through the control of minerals they would find. Southern Rhodesia, as it turned out, was not blessed with huge mineral deposits. When this became evident the European settlers turned their attention to agriculture. Successful agriculture depended on a number of factors, the most important being fertile land, cheap and abundant labor, credit for purchasing inputs—seeds, fertilizers, etc.—and transportation infrastructure (roads, railway) to market goods produced.

In 1930, the Legislative Assembly passed the landmark Land Apportionment Act which divided all of Zimbabwe between Europeans and Africans, providing each racial group with roughly the same amount of land. That is, although the native born Zimbabweans outnumbered the Europeans by 60 to one, the Europeans were given roughly the same amount of land as the Zimbabweans. Moreover, the land allocated for Europeans was overwhelmingly in the most fertile and well-watered areas for Zimbabwe, while the Native Reserves were allocated less fertile and often semi arid land. This policy was necessary for economic prosperity of the European settlers.

In addition to the land policy, the Legislative Assembly also passed a series of laws which made it very difficult, if not impossible, for Zimbabweans to compete with European farmers in producing and selling the major corps of tobacco and maize (corn).

The Legislative Assembly expanded on the unfair tax policies that had been instituted by the BSAC. In addition to increasing the amount of the “head” or “poll” tax, levied (charged) on every adult male, they also introduced taxes on animals and on licenses that Zimbabweans were forced to purchase. These taxes (which were imposed without any representation) had the dual effect of raising revenue for the government, but more importantly, of forcing young men to leave the reserves and find work on farms on mines in order to pay their tax obligation. Taxes provided European farmers with the cheap labor they needed in order to successful farmers.

The legislation action taken by the Settler dominated government of Southern Rhodesia in the 1920s and 1930s established a system of severe racial discrimination and segregation that guaranteed European dominance of the politics and economics of Southern Rhodesia over the next 50 years. Of course, during these years the economy of Southern Rhodesia underwent considerable change. While agriculture continued to be the cornerstone of the economy, diversification took place as the commerce and manufacturing industries developed in expanding urban areas such as Salisbury (now Harare) and Bulawayo particularly in the years after World War II when the Rhodesian economy under went a period of sustained growth.

Central African Federation (1953-1963)

Do you remember that during the era BSAC rule (1894-1923) that the Company also had control of two neighboring colonies, Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland (Malawi)? In 1924, when the BSAC gave up its control over Southern Rhodesia it also gave up control of its other two colonies. However, unlike the situation in Southern Rhodesia where the European settlers were given considerable political power, in the northern colonies the British colonial office took over political (and economic) control.

In the late 1920s large deposits of copper, lead and zinc were discovered in Northern Rhodesia. The development of the mining industry in Northern Rhodesia generated a great deal of money for European controlled mining companies. The settler government in Southern Rhodesia became interested in potential for revenue generated by the mining industry in their northern neighbor. This interest grew after World War II when Southern Rhodesia was looking for ways in which they could obtain resources to sustain their economic growth. Because of this interest the government of Southern Rhodesia, with the full support of the settle business community, investigated the possibility of incorporating Northern Rhodesia, a country nearly twice its size.

How do you think Africans in Northern Rhodesia responded to these overtures from the south? Based on what they knew about the treatment of Black Zimbabweans, they were not pleased with the idea of merging with Southern Rhodesia. Although they were a colony of Britain and had virtually no political power, the British government was sensitive to the concerns of the Zambian population and rejected the idea of a merger between the two territories; a merger which would expand the power and influence of the European settler community.

The British government submitted an alternative plan that called for the creation of federation between the two Rhodesias and Nyasaland. A federation would allow for greater cooperation between the three colonies, including economic integration, while allowing each territory to maintain some of its own political autonomy. Africans in all three colonies were opposed to the idea of a federation, but the white settler populations in each territory supported the concept and in 1953 the Central African Federation of the Rhodesias and Nyasaland came into existence.

The Federation benefited Southern Rhodesia’s economy because it provided much needed revenues from the mining industries in Northern Rhodesia. Politically, however, the Federation was a problem for the settler government The Federation, which gave most power to Southern Rhodesia, became the focus of African nationalist opposition in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. By the early 1960s the nationalist opposition became too strong for the British to ignore. They were forced to dissolve the Federation in 1963 and in 1964 Nyasaland became independent as Malawi and Northern Rhodesia became the independent nation of Zambia.

With the demise of the Federation and the independence of Malawi and Zambia, the European settlers in Southern Rhodesia were determined that they would maintain their control of power regardless of the fact that many African colonies were becoming independent nation-states. In 1961 right-wing European settlers formed the Rhodesian Front, a new political party whose agenda was the maintenance of absolute white control of Southern Rhodesia. In 1963 under the leadership of Ian Smith the Rhodesian Front overwhelming won a national elections—an election, of course, in which only whites could vote.

Then, on November 11, 1965 Ian Smith unilaterally declared the independence (UDI) of the nation-state of Rhodesia, promising the Europeans who comprised less than 10 percent of the country’s population that the Rhodesian Front government would institute policies that would guarantee that Black Zimbabweans would not govern Rhodesia, in his words, “not in one thousand years.”

African Resistance

The brutal suppression of the Chimurenga up-rising in the Shona speaking areas of Zimbabwe effectively reduced open African resistance to colonial rule Moreover, policies enacted by the settler dominated government in the 1930s and 1940s solidified European control of all aspects of Rhodesia’s political and economic systems At the same time, the land and labor policies of the Rhodesian government weakened the social structure and fabric of Shona and Ndelele societies, making organized resistance difficult, if not impossible.

In spite of these obstacles, there were notable attempts by Zimbabweans to express their deep dissatisfaction with the way that they were treated by the European settlers. These expressions took a variety of forms. In 1927 mining and industrial workers formed the Industrial and Commercial Union (ICU), the first trade union for Africans in Zimbabwe. The goal of the ICU was to improve the conditions of African workers in the country. How do you think the settler government responded to the ICU? They made the ICU an illegal organization and arrested the leadership, imprisoning some and sending others into exile in South Africa and Nyasaland (Malawi).

The Rhodesian agriculturally based settler economy of Rhodesia was dependent on a large cheap labor force Given this dependency and fact that Zimbabweans who were forced to work on European farms did not do so willingly, why not organize the farm workers as a way to protest mistreatment? Organization of farm workers was not easy given the migratory nature of farm labor up until the 1950s. Remember, the government imposed a system of taxes to force Zimbabweans to work for European settlers. Tax money could be earned by working for 3-6 months year. Consequently, a worker stayed on a given farm for only a short period of time, making organizing workers difficult. Moreover, if a group of workers did express dissatisfaction the European farmer could dismiss the workers, knowing that there was an abundant reservoir of labor to replace any dismissed worker.

For workers to effectively organize themselves they have to be in a position in which they can negatively impact their employers by going on strike The first effective strike of Zimbabwean workers took place in 1945 among the railway workers. Unlike, European farmers, the railway was dependent on workers who they trained for semi-skilled positions. Training took time and money. Consequently, the railway needed a permanent workforce, not a temporary-migratory work force that changed every six months. The railway was dependent on semi-skilled Zimbabwean workforce and could not easily replace dissatisfied workers if they decided to go on strike.

Given their relative position of strength, when the rail workers went on strike in 1945 the railway management and Rhodesian government had to take them seriously. Of course, the authorities tried to squash the strike and in the end while the strikers did not get everything they wanted, they won an important victory. . .the right to organize into a trade union that would have the right to negotiate with management.

The 1945 rail strike was followed in 1948 with a general strike by urban workers in Salisbury, Bulawayo, and other urban areas. These strikes focused primarily on important economic issues—wages, the need for adequate housing, water supply, health care, and education. While the strikes were clearly political in that they challenged the colonial system that benefited Europeans and exploited Zimbabweans, the strikers did not make explicit political demands such as right of political participation.

In the 1950s, Zimbabweans became more politically oriented in their interactions with the settler government. The politicization of Zimbabwe in the 1950s was the result of both external and internal factors. In other parts of Africa (and colonized areas of Asia and the Caribbean) the 1950s was time of nationalism and resistance to colonial rule. You can review these anti-colonial movements in Africa by linking to Module Seven B, Activity Four. African nationalism and the movement towards independence across Africa, encouraged Zimbabweans to more actively engage the political system by making demands for increased African participation in the political system that had completely excluded them since 1898. For example, Robert Mugabe, who became the first Prime Minister of independent Zimbabwe in 1980, lived for a number of years in the late 1950s in Ghana, which became independent in 1957. Mugabe, who returned to Zimbabwe in the late 1950s, was very much influenced by his experiences in Ghana.

There were also important internal factors that stimulated the rapid politicization of Zimbabwe in the 1950s and 1960s. During the period following World War II the Rhodesian economy diversified and became more urban based requiring workers who would live permanently in growing urban areas. Urbanization resulted in increasingly educated Zimbabwean workforce that was very dissatisfied with the severe discrimination that they faced daily and who recognized that meaningful change could only occur through actively engagement in the political system.

In 1955 a group of young educated Zimbabweans formed the City Youth League, the first overtly political organization that articulated a political agenda for the African population of Zimbabwe. The City League called for the expansion of the franchise to include Africans and the establishment of a number of African seats in the National Assembly. This was not a call for independence, but it frightened the Rhodesian regime which tried to suppress the activities of the Youth League.

In 1957, the young Zimbabwean nationalists who had formed the City League joined with other nationalists to initiate a new nation-wide political organization, the Southern Rhodesian African National Congress (SRANC). The SRANC joined with nationalist leaders from neighboring countries (Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland) which were part of the Central African Federation formed in 1953, to demand an expansion of political rights for Africans. In 1959, there were a series of political protest throughout the Federation. The Federal government, based in Salisbury, declared a state of emergency throughout the Federation In Southern Rhodesia, the SRANC was banned and 300 members were arrested and jailed.

The mass arrests did not deter the Zimbabwean nationalists. In January, 1960 the nationalist leaders who had not been jailed formed a new political organization the National Democratic Party (NDP). 1960 was a key year in the political history of the entire continent Seventeen French and British colonies gained their political independence. These events caused great optimism among the nationalist leaders in Zimbabwe who came to believe that majority rule was a possibility even in European settler controlled Rhodesia.

The path to political independence was not an easy one in Zimbabwe. It took twenty more years, including a decade of armed resistance, the Second Chimerenga, until Zimbabwe began independent in 1980. The NDP was banned in 1962, but it was immediately replaced by the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU). There was a disagreement over how much Zimbabweans should comprise in their negotiations with the settler regime within the nationalist movement in 1963 which led to the formation of a second political organization, the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). In 1964 the government of Ian Smith banned all African organizations, arrested and jailed much of their leadership, although some nationalist leaders escaped capture and went into exile in neighboring Zambia (which became independent in 1964) and Tanzania.

For the first five years after Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 the nationalist movement was effectively but harshly suppressed. By 1970 the exiled leadership of both nationalist groups had formed armed liberation movements that operated out of neighboring Zambia and Mozambique. The Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) was the armed wing of ZANU. After 1974, when Mozambique won its independence, ZANLA operated from bases in Mozambique ZAPU formed the Zimbabwe Peoples Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) which operated from bases in Zambia and Botswana.