Tanzania in the Indian Ocean World

Introduction

In this Activity you will learn about the history and current status of a Tanzanian minority called “Tanzanians of Indian Descent.” At the end of this activity, you will

- Know more about the complexities of identity

- Have a better understanding of the global linkages in which Tanzania has been involved for thousands of years

- Have a firmer grasp of how segregation affected race relations in Tanzania

- Be able to identify some common aspects of Indian and Tanzanian cultures

Who are you? Nationality, Ethnicity, Heritage, and Identity

In the United States, we are used to hearing words to describe people like “Latin-American,” “African-American,” or “Asian-American.” What do these descriptions really mean? The United States is primarily comprised of people who trace their heritage to other places around the globe. According to United States law, anyone born on U.S. soil is a U.S. citizen, no matter where their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents may have come from. Look around you. Chances are your teacher, most of your classmates, and maybe even you have ancestors who migrated (voluntarily or involuntarily) to North America from a different continent. Celebrating and honoring that diversity is an important part of American culture.

We use categorical words like “nationality,” “ethnicity,” “heritage” and “identity” to describe some of the different ways that people define themselves. Each of these words can mean many different things to different people, and their meanings often intertwine and overlap when we use them to describe other human beings. We will examine some of these different definitions now.

Nationality—Nationality is usually (but not always) associated with the name of a country. It is the country where a person was born, has legal citizenship, or feels most at home. Some people have more than one nationality. The number of people claiming multiple nationalities has increased in recent years due to globalization and easier, cheaper transportation.

Ethnicity—A person’s ethnicity is usually the culture, sometimes called the “ethnic group,” with which someone identifies themselves. Ethnicity can be based on things like language, religion, cultural practice, location, or heritage. Like nationality, ethnicity is sometimes associated with the name of a country, special area in a country, or region of the world. Some people view their nationality and their ethnicity as the same thing, while others prefer to separate the two. In the same way that someone can claim multiple nationalities, a person can also belong to many ethnic groups.

Heritage—So far, you have learned about a type of heritage referred to as “political heritage” in Module Ten. When they are not speaking in a political sense, people often use the word “heritage” to describe the nationality and ethnicity of their parents or grandparents. In a world where people often move and resettle, many children are born in different countries than their parents. Even though their children live in a different place and community, parents can still choose to pass the cultural traditions they grew up with along to their children. Language, stories, ceremonies and holidays, recipes, art, songs, dress, religion, and ways of viewing the world can all be part of someone’s heritage.

Identity—Identity is a word that encompasses all of the words above. Identity can describe any part of what makes someone a “self.” This includes their nationality, ethnicity and heritage, but also their location, occupation, history, physical characteristics, personality, interests, gender, age, or position in a particular social group. A very important thing to remember is that anyone’s identity is always multiple and always changing. For example, it is possible for someone to be a female, a Californian, a sister, a daughter, a Latina, a Roman Catholic, and a skateboarder all at once. Later on that same person might become a New Yorker, a musician, a mother and a businesswoman, and she may still identify herself as a daughter, a sister, a Latina, and a female, but the level or intensity of importance that she assigns each of these identities may change over time.

It is important to remember that our identities—national, ethnic, and cultural—are open to change. Just as a person can have more than one national or ethnic identity, a person’s national, cultural, or ethnic identity may change once, or even several times, over their lifetime. For example, a person born in Tanzania may as a young adult immigrate to the U.S.; by the time she is middle-aged she may think of herself primarily as an American. Thus social identities can be thought of as being fluid—and not necessarily permanent.

Make a list of ten words (nouns and adjectives) that describe your nationality, ethnicity, heritage and identity, and switch lists with a classmate you do not know well. Do any of the words on your classmate’s list surprise you? Can any of these words apply to more than one of the categories above? Can you guess the category for which your classmate listed each word?

Hopefully this exercise has shown you how much the categories of nationality, ethnicity, heritage, and identity depend upon each other—so much so that they are not always easily distinguishable from one another. It is important to realize that the way that any person uses these words also changes according to the political and social situation in which they find themselves. For example, if you met someone from another country, you might call yourself “American,” “North American,” or even “Western,” depending on where that person is from and what they might know about your country. If you meet another American, you may instead describe yourself by the state you come from or your home-town.

You learned in previous modules that the African continent is full of diverse cultures, each with its own history, customs, and practices. You also learned that migration has been one of the key factors contributing to African diversity over the centuries. Like most North Americans, some African groups can trace their heritage to places outside of the African continent. One such group present in the country of Tanzania is a community who call themselves “Tanzanians of Indian descent.”

The following photographs were taken from a colonial-era parade celebrating different kinds of Tanzanians. Are there public activities in your town which celebrate the different kinds of people who live there? How are these activities similar or different from the pictures you see below?

Source: British National Archives

Tanzanians of Indian descent celebrate their heritage in a parade.

Tanzanians of Indian Descent: Pre-Colonial and Colonial History

In the history portion of this module you learned that people from what are now the countries of India and Pakistan had established trading relationships with people on the African continent for centuries before the European colonial powers ever arrived. Some important experiences in world history occurred because of this interaction between Indians and Africans. For example, Mahatma Gandhi, the father of Indian independence, developed his principle of non-violent civil disobedience while living in South Africa, 1893-1914. The beliefs he established while living in South Africa were so powerful that they existed long after Gandhi’s death, and went on to influence people like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the famous leader of the American Civil Rights Movement. You can learn more about Gandhi’s time in South Africa here. (To read about Gandhi and passive resistance in South Africa see South Africa History Online at http://www.sahistory.org.za/pages/people/bios/gandhi,m.htm and http://www.sahistory.org.za/pages/governence-projects/passive-resistance/menu.htm. You can also search the site for the history of Indians in the country.)

India’s first contact with present-day Tanzania probably occurred on the island of Zanzibar, about 70 kilometers from the port city of Dar-es-Salaam. You might remember Vasco Da Gama’s involvement with East Africa from the history of Tanzania. By the time Da Gama landed on the East African coast in 1497, Indian and Arab traders were already well-established in the region. In the winter months, Indian traders and merchants would typically leave from Porbandar or Diu—Western ports located in what is now the state of Gujarat, India—their ships loaded down with colorful woven textiles, spices, and other goods to trade and sell in East Africa. These long, narrow ships, called dhows, had the shape and sails especially designed to ride the monsoon winds all the way to Africa.

Like most sailing expeditions at the time, the trip between Western India and East Africa could be dangerous. Passengers and crews faced pirates, illness and stormy seas, and at times found themselves caught up in wars between other countries. They would usually land in Zanzibar, where they could exchange their wares for spices and ivory, a material in high demand in India but which was not readily available. As time passed, some of the Indians who landed in Zanzibar discovered that they could make better (and make less dangerously) money by setting up permanent warehouses where typically traded materials like textiles, spices, and ivory, could be bought and sold. The picture below shows what collections of ivory ready for shipment might have looked like.

As Indian-run businesses in Zanzibar increased in number, rumors spread back in India that East Africa was a prime place to gain employment and wealth. Many young boys and men from the Gujarati coast worked on trade ships in exchange for a ride to the famous island of Zanzibar where they would seek employment. It became a common practice for these men to return to India later on in their lives, bringing servants and wives back with them on their return journey to Zanzibar. The picture below shows the family of Yusufali Karimjee, a prominent businessman and community figure in Zanzibar and Tanganyika. You will learn more about him later on in the lesson.

The 1800s: Indians move into Tanganyika

While trade boomed on the Island of Zanzibar, Indian businessmen on the coast of the Tanganyikan mainland began to set up posts from which caravans traveling into the interior of the continent could procure supplies before heading off on their trade safari. This particular “caravan supply business” took off when the Sultan of Zanzibar, Sayyid Said, made it more expensive to organize caravans from the island by increasing taxation on them. The German occupation of Tanganyika, which began (officially) in 1888, also encouraged Indian businessmen to move further into the interior of Tanganyika. The German administrators began to set up schools, missions, clinics, and railways throughout the Tanganyika territory without having trained the Tanganyikans how to run these facilities. With their infrastructure in place, the Germans realized that they were short of skilled workers in several occupations: teaching, engineering, medicine, craftsmen, etc. They began to bring in Indians from the coast to fill these positions.

The East African Railway, built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, presented another opportunity for Indians to settle in East Africa. The British, who administered both Tanganyika (after World War One) and India, employed nearly 40,000 Indians for railway-related work. Many of these contract workers, seeing opportunities for new business, stayed on in Africa after the railway was completed. These were some of the first businessmen to bring large amounts of coastal commodities into the Tanganyikan interior.

Indian Tanganyikans and Indian Zanzibaris under British Administration

Outside of trading relationships, it was probably British colonization that most enabled the majority of Indians to settle in what is now Tanzania. As a result, Indians of many different ethnicities, classes, castes, and religions call Tanzania home. The diversity of this community will be discussed later on in this lesson. For now, we will split the colonial Indian Tanzanian community into two broad categories: People in the group that we will call “higher-class” Indians were educated intellectuals or wealthy businessmen with high status in the community. Those higher-class Indians who belonged to the Hindu community also usually came from one of the higher castes of Hindu society. People in the group that we will call “lower-class” Indians usually migrated to East Africa to work in manual labor or to accompany higher-class Indians as servants. Often, lower-class Indians belonging to the Hindu community were members of a lower caste as well.

This distinction between lower and higher-class Indians has played an important role in Indian Tanzanians’ history. In Module Ten, “African Politics and Government,” you learned about a colonial tactic known as “divide and rule.” The British considered higher-class Indians racially “superior” to lower-class Indians and Africans. For this reason most of the administrative, trading, or infrastructural work which British colonizers could not (or would not) carry out on their own was taken up by higher-class Indian middlemen. The British Administration’s favoring of Indians is widely regarded as a kind of divide-and-rule tactic, and it has had major repercussions on the racial relationships within Tanzania.

Compare the two family portraits below. One, as you have read, is of the Karimjees, a wealthy business family. The other picture is a portrait of a working-class family taken by a traveling photographer. How do these pictures illustrate the class differences in the Indian community?

The legacy of favoring higher-class Indians over lower-class Indians and Africans began early in British colonial involvement. In 1931, the British administration of Tanganyika passed the Credit to Natives Ordinance Act, which essentially kept African Tanganyikans from opening businesses of their own by making it impossible for them to borrow money. In colonial times, higher-class Indians had easier access to wealth, education, health services, and mobility than lower-class Indians or Africans. Higher-class Indians were also more likely than Africans to get work in the coveted Tanganyikan Civil Service, the branch of colonial administration that coordinated government regulated activities like education, police and courts, transportation and health services in the territory. On Zanzibar, Indian and Arab traders also had great advantages compared to African Zanzibaris. Not only did they tend to dominate trade on the island, but, due to the high profits they earned, these minority groups were also able to buy large tracts of land to plant cloves and other cash crops. African laborers would then harvest the cash crops.

One of the young boys in this picture described it as showing the “family and its employees.” Locate the one African in the photograph. He was a night-watchman wearing his uniform. What does this photograph and its context tell you about race relations in early 20th century Tanganyika?

Other racial divide-and-rule tactics were more subtle, such as the racial segregation of Dar-es-Salaam. In the city of Dar-es-Salaam, Europeans tended to isolate themselves in an expensive suburb-like area known as Oyster Bay. Likewise, the British colonial administration encouraged higher-class Indian, Arab, Pakistani, and Chinese businessmen to set up shop in the nicest part of downtown Dar, called City Center. The high prices of real estate in City Center kept most African and lower-class Indian Tanzanians from moving into this area. As a result, lower-class Indians and the vast majority of Africans living in Dar-es-Salaam stayed in crowded neighborhoods further in from the port and the center of the city. Although Dar’s racial segregation was not nearly as strict or as encompassing as that practiced in Apartheid South Africa, the obvious differences between high-class Indian and African living spaces made it that much harder for African and Indian Tanganyikans in Dar-es-Salaam to build relationships based upon respect.

Little is known about the picture above, but we can infer that it was taken at a school, probably during a science experiment or demonstration. These students may all look similar at first glance, but note how the young boy in front and the teacher are wearing a special type of turban which marks them as members of a Sikh community, while other male students are not wearing one. The picture shows how, even in a classroom where the students all look like they have the same ancestry, they actually come from diverse backgrounds and religions, and probably speak different languages as well.

Imagine that your own class was in this picture. How many different kinds of communities, languages, and religions would be represented?

The following map was shows the building zones enforced in Dar-es-Salaam while under British mandate. Within each zone, the British stipulated rules about the kinds of buildings (and therefore the kinds of people) allowed to be there. According to laws at the time, Zone 1 was for “residential buildings of European type only,” Zone 2 for “residential and trading buildings, and Zone 3 was for “native quarters.”

Can you locate the three building zones on the map? What differences can you identify between these zones?

The following photograph is a picture of part of modern-day Dar-es-Salaam from above. What differences do you see between the left and right sides of the photograph? What can this photograph and the map before it tell us about segregation in the city? If you saw an old map and current photograph of your city, what do you think you would see?

Indian Tanganyikans and Zanzibaris in the Independence Movement

In spite of spatial and cultural segregation, many Indian Tanganyikans were also involved in the independence movement. A group called the Asian Association worked in close conjunction with the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) to negotiate Tanganyika’s independence from Britain. Even as far back as 1930, an Indian lawyer named Ramakrishna Pillai established himself as an ally to the African Association of Tanganyika. In addition to offering legal advice, Pillai is best known for encouraging the Association to push for representation in the colonial government. The colonial administration was reportedly very angry with Pillai for offering support and feasibility to the idea of Tanganyikan independence. Despite the efforts of Pillai and many others, it took a long time before non-Europeans received representation in the Colonial Administration. Records indicate that fifteen years later, in 1945, only two Africans and one Asian had been nominated to the Tanganyika Colonial Council–and their status was “unofficial.”

Asians in Tanganyika and Zanzibar faced a challenge in the late 1940’s when India and Pakistan achieved independence from Britain. By this time, many Asian families had lived in Tanganyika for generations. Even though some families maintained ties with their ancestral countries, most Asian Tanganyikans and especially Asian Zanzibaris claimed Africa as their only home. Because of the events in India and Pakistan, these families were suddenly forced to choose if they wanted to be Indian or Pakistani citizens or remain under British protection. Many chose the latter. Even the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of the Ismaili community, ordered his followers to revoke their status as Asians and become African. In the 1950’s, members of the Ismaili community took measures to make their cultural presence more acceptable to other Tanganyikans.

A number of other Indians are well-known for their contribution to the independence movement and the creation of the new nation’s government. Some of them are pictured here along with their stories:

Amir Jamal, a second-generation Tanzanian of Indian descent, participated in the independence movement from its very beginning. From 1961, a year before Tanganyika’s independence, until 1989, Jamal served as Minister of Finance, Commissioner for Planning, Minister for Communications and Works, and Minister for Trade and Industry. He also served for years as Tanzania’s Ambassador to the United Nations. Jamal was highly respected for his integrity and selfless service to the nation.

KL and Urmila Jhaveri were a married couple dedicated to independent Tanganyika. KL served as Dar-es-Salaam’s first representative in the National Assembly, and he later became president of Tanzania’s Law Society. Like Sophia Mustafa, Urmila Jhaveri dedicated her life to women’s activism in Tanzanian politics. Described as a mediator and peace-maker, she also launched a number of activities designed to bridge the gap between Dar-es-Salaam’s ethnic communities.

Indians in Socialist Tanzania

Tanzania’s socialist period posed difficulties for many Indians. The nationalization of businesses, industries, and buildings greatly affected the Indian community’s ability to make a living, and many Indians emigrated out of the country as a result. Many Tanganyikans mistook Nyerere’s vision of socialism based on “African” values to mean that non-Africans were no longer welcome in the country. Nyerere reminded African Tanganyikans that assuming racist attitudes towards others in the country would make them no better than their former colonizers. He made the strict point that the struggles between the different Tanzanians had to do with class instead of race. In a speech debating the status of Asian citizenship in the National Assembly, Nyerere took the question head-on:

“I have said sir, because of the situation we have inherited in this country, where economic classes are also identical with race, that we live on dynamite, that it might explode one day, unless we do something about it. But positively not negatively.”

But the problems surrounding racial groups persisted. In Zanzibar’s revolution, hundreds of Arabs and Asians were killed and many more fled the island for the mainland. Neighboring Uganda, under the dictatorship of Idi Amin (1971-1979), expelled Indians by the thousands from the country, many of whom sought refuge in Tanzania. By the time Tanzania adopted a more capitalist model and re-privatized its industries, the Indian population in the country had changed a great deal.

There are some interesting aspects to the changes that have occurred in the Indian Tanzanian population. For example, a large number of Indians who left Tanzania during the socialist period migrated to Toronto, Canada. There, they have formed a number of groups who gather to celebrate their unique heritage as Africans of Indian descent. At these meetings group members eat Tanzanian food and speak their own dialect of Swahili. Many return on a regular basis to visit family members, and some have re-established their businesses in Dar-es-Salaam. Like many ethnic groups in the United States, Tanzanian Indians have displayed an ability to move from place to place without losing the vital pieces of their multi-cultural heritage which make them so unique as a community.

Explore the website of the Tanzanian Goan Club of Toronto above. What are some of the defining features of this group? How do you think they have been able to manage to stay in contact with one another throughout their long history? If you founded a similar “heritage” club, what would you name it? What kinds of food would you eat and languages would you speak at the meetings?

Tanzanians of Indian Descent Today

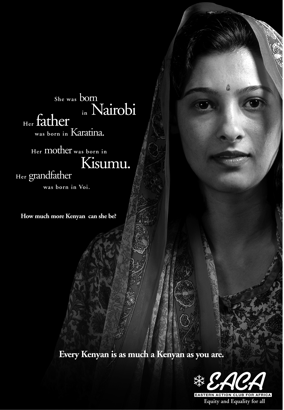

In many ways, Indians are still fighting for a legitimate place in East Africa, as the poster above referencing Indians in Kenya shows. However, recent studies have shown that the number of multi-lingual, multi-ethnic, and multi-racial families is on the rise in Tanzania, indicating that mixture and communication between different groups is now a common occurrence. Even though they may at times feel like isolated peoples, Tanzanians of Indian descent and Tanzanians of African descent share many cultural attributes. Indian film and fashion are popular in Tanzania, and Africans have adopted a variety of Indian foods as their own. Without even knowing it, Swahili speakers use a number of Hindi-Urdu based words in everyday speech, and the Indian influence on Tanzanian music is undeniable.

Conclusion:

This module has helped you to understand the experience of a community in Tanzania—but it is important to remember that Tanzanians of Indian descent are just one minority in a country which is proud to be made of many different kinds of people. Each of these groups has just as vibrant a history and just as important a part to play in modern Tanzania, and it has taken the contribution of all kinds of Tanzanians to make the country what it is today.

This is the final activity in this module. Go on to Module Twenty Seven, return to the Curriculum, or select from one of the other activities in this module.